Satellite Image from Google Earth

It’s hard to talk about because it shouldn’t have happened.

Chris Theil was planning to intern with a music festival over the summer. He divided his time between the cello and guitar while studying music production at Hocking College.

Hannah O’Harra-Brown, who was studying physical therapy at Hocking, worked at Bagel Street Deli and made sure to tell her mother how much she loved her life.

Brad loved Ohio University from the start, even though, as he puts it, his “focus was not academics by any means.”

The three didn’t know each other. Like a lot of college students, they were living in the moment.

Then came hell.

In May 2008, Theil was found in the bathroom of a Riverpark Towers apartment. He was hunched over the bathtub; his girlfriend, an OU student, lay beneath him in the water. They both died at 22 years old from an accidental overdose of heroin and alcohol during Moms Weekend.

More than two years later, in December 2010, O’Harra-Brown was drinking and took oxycodone. The 21-year-old died in her sleep.

And in 2012, Brad, who asked to only be identifed by his first name for this report due to the stigmas associated with addiction and recovery, started to abuse Vicodin. Less than a year later, high on heroin for the first time, he walked down Court Street knowing he would probably use again.

He spent his last few months in Athens driving up Route 33 to Columbus a few times a week to buy heroin. He graduated in 2013.

Nobody else who took those rides with him graduated.

“When I was using, I never even thought about it,” Brad said. “You don’t realize the gamble that you’re taking with your life.”

The epidemic of prescription opioid painkillers, heroin and resulting accidental overdose deaths can be just a faraway headline — someone else’s tragedy, or something you’re completely unaware of — until you’re on the other side of it.

Some people told O’Harra-Brown’s mother, Melissa, that she could attribute Hannah’s death to a freak accident. It was just a second of her daughter’s life, a horrible mistake that could have been made by any well-meaning college student.

It never gets easier to talk about, Melissa O’Harra-Brown, a nurse practitioner in Logan, said. But she won’t hide what happened.

Just like it’s hard for Brad to talk openly about his addiction, now that he’s been clean for three years. Just like it has been immensely frustrating for Lauren Kuhn, Theil’s younger sister, who lost her brother-in-law, too, to an accidental overdose death in November.

“We all want to think that we’re somehow smarter, better, brighter, that it would never happen to us,” O’Harra-Brown said.

Through her tears — as painful as it may be — she’s one of many who asks that society starts talking.

There were more than 33,000 overdose deaths involving an opioid in the U.S. in 2015.

For context, that’s about double the size of the undergraduate student population enrolled at Ohio University’s Athens campus for Spring Semester 2016: 16,974 undergraduate students.

That’s a particularly grim statistic, especially when one considers that those 33,000 deaths occurred across the country. About 2,500 of those 2015 opioid overdose deaths were in Ohio.

Description: Fentanyl is a prescription opioid typically used during anesthesia or to treat patients with severe pain, though recent overdoses have been connected to illegally produced, trafficked fentanyl, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The drug is highly potent and is sometimes mixed with heroin to amplify its effects.

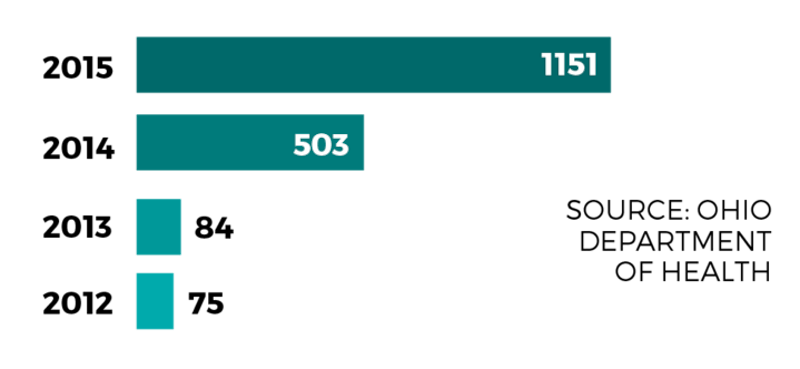

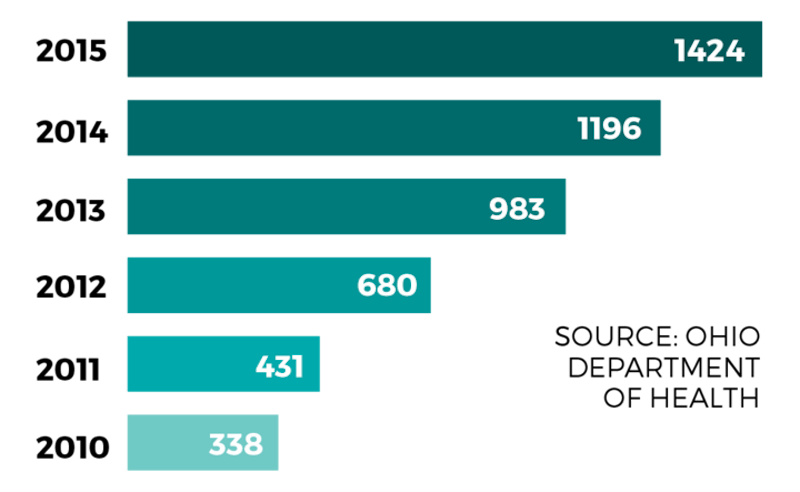

Description: Prescription opioid drug users began to turn to heroin due to its increasing availability throughout Ohio. Additionally, prescribing guidelines began to strengthen, according to a 2014 report from Ohio Gov. John Kasich’s Opiate Action Team, making heroin an often cheaper alternative. There were 87 heroin deaths in 2003, according to data from the Ohio Department of Health. The overdose death rate for heroin was more than 16 times that in 2015.

There is no short way to describe the opioid epidemic in full, except, perhaps, that it was triggered by the lax prescribing guidelines attached to legal painkillers, such as oxycodone and hydrocodone.

Years later, that led to widespread heroin and prescription opioid addiction, spikes in crime, the advent of so-called “pill mills,” doctor shopping and overdose deaths. Ultimately, dozens of health providers, law enforcement officers, advocates and family members of addicts were thrown to the front lines of a problem that seemed to have no true end in sight.

Some medical professionals say the epidemic is rooted in a letter to the editor published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1980, wherein Jane Porter and Dr. Hershel Jick shortly summarized that fewer than 1 percent of the 11,882 patients they treated with narcotics became addicted.

Then, a decade later, pain gained recognition as the “fifth vital sign,” despite its inability to be properly measured. To treat that chronic pain, doctors were increasingly expected to prescribe opioids.

One February morning, Athens City-County Health Commissioner Dr. James Gaskell attempted to describe the history of the problem.

He thought back to when he was a pediatrician in the early ‘90s and an Ohio Medical Board member came to him and other physicians at OhioHealth O’Bleness Hospital, saying they weren’t prescribing enough painkillers because they were afraid they would be looked upon unfavorably. And those opioids were once feared for their particularly addictive chemical compounds.

What happened next, he said, was an overreaction on the medical field’s part.

“They were trying to make the point that we were letting people die in pain, that we needed to provide pain relief,” Gaskell said. “We took it more generally, and that was sort of the beginning of it all.”

The opioid drugs mimic endorphins by attaching to proteins referred to as “opioid receptors” to reduce the perception of pain in a patient, often producing a sense of well-being and relief.

However, repeated use can inhibit the brain’s ability to feel pleasure naturally, lessening the drug’s effect and prompting users to take a higher dose as their tolerance increases. As time goes on, some opioid users are unable to feel comfortable without the drug.

Heroin, which has a similar pharmacological makeup, also activates those same opioid receptors. The drug began to spike in popularity as the street worth of prescription painkillers steadily rose.

“That’s why you think, you know, ‘What the heck are they doing?’ They steal from their parents, they’re ignoring their kids. But that addiction is so strong that they’re going to do what they have to do to continue that addiction,” Athens County Sheriff Rodney Smith said.

Now, it’s more than just addiction to the typical prescription opioids, which actually saw a slight decrease in overdose deaths in 2015.

Heroin and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl — considered 30 to 50 times stronger than heroin — have driven the epidemic’s narrative toward drugs that kill quicker and with a greater frequency.

And if you want to see where the needle on the epidemic began to switch from a handful of addicts to an onslaught of overdose deaths, look no further than the data that Dr. Joe Gay, executive director of Health Recovery Services in Athens, collects with widely acknowledged fervor.

“I love numbers, always have,” Gay said.

A member of the 317 Board first approached him in 2007 to ask if he had seen a spike in heroin use. Gay told the board member he hadn’t. At the time, the data just wasn’t there.

When a supervisor came to him shortly after in 2008 and reported an increasing number of patients seeking help for addictions to heroin, Gay started crunching the numbers. Clinicians told Gay he had “jinxed” them. Heroin just didn’t happen in Appalachia, where he was used to treating patients for alcoholism.

What happened next “scared the devil” out of him, he said — especially since people were injecting the drug.

In spring 2010, Gay looked at data from the Ohio Department of Health that showed the relationship between opioids prescribed and overdose death rates in the state from 1997 to 2007 and ran a correlation coefficient — a measure of the linear relationship between two variables, with a perfect, positive relationship being 1.0.

Any student who has taken a basic statistics course knows: Correlation does not necessarily imply causation. But the correlation between opioid drugs distributed per 100,000 and accidental drug overdoses was .979.

Gay assumed he had to be wrong. It was just too high. He called Orman Hall, who would go on to become the director of the Ohio Department of Alcohol and Drug Addiction Services, and left a voicemail with the results to double-check. He soon heard back from Hall that it had to be “bulls--t.” Gay checked again. Then Hall calculated the same result.

“That’s how closely related prescribing was to the death rate,” Gay said.

After her older brother’s overdose death, Lauren Kuhn attended another funeral for a young addict. Then another. Then another.

She watched as four young lives ended due to opioids in the three months after her brother, Chris, was found dead in May 2008.

Theil’s addiction started with a prescription, she said. Like a lot of teenage boys in Dublin, where they grew up, he was into skateboarding and snowboarding. As a result, he secured a handful of injuries. He broke his wrist his freshman year of high school and was prescribed Percocet and Vicodin. He started using heroin about a year later.

He bounced in and out of treatment several times, and his arm was nearly amputated by doctors after he continued to shoot into an infected area. But then, Kuhn said, he finally got clean, went to college and even called her the night of his death to talk about his internship.

“For as well as he was doing, we kind of thought it was in the clear,” Kuhn said.

Brad, too, said he has attended more funerals than some one his age should have to.

By the time he started abusing Vicodin in 2012, he said painkiller use had exploded on campus. Less than a year passed between his first time taking an opioid drug and the realization that he had become a “full-blown” heroin addict.

When people jumped to heroin, that’s when the problem became harder to ignore: People started dying.

But even then, at the same time that more earth was being hollowed across Ohio for young men and women who died from opioid addiction, Kuhn remembers being frustrated by how little people spoke of it — especially in the quiet, well-off Dublin community where she was raised.

It’s been nine years since her brother died, and for so long she has felt alone in recognizing just how devastating the epidemic has become. Only in the past two years have people really talked about it.

“There’s so much denial,” Kuhn said.

Some addicts still think their fate is in their own hands. Kuhn’s brother-in-law left three children behind when he died, she said, convinced he could beat his addiction before heading to treatment. Others can’t get access to care in the first place. Theil’s best friend died of an overdose too, waiting for a spot in a treatment center.

As a result of those deaths, states and municipalities continue to file lawsuits against some of the country’s largest opioid drug manufacturers, like Purdue Pharma — the manufacturer of OxyContin — Johnson & Johnson and Endo International, while others, such as West Virginia, have sued distributors of the drugs, such as McKesson Corp.

In 2007 — more than a decade after OxyContin was introduced to the market — one such case against Purdue Pharma resulted in three executives pleading guilty in federal court to allegations that they had misled patients, doctors and regulators through false marketing about the adverse effects of OxyContin, for which they were forced to pay $600 million in fines.

“It was not enough money to make a difference,” Gaskell said of the lawsuit. “Unfortunately, it’s going to fall to the taxpayer to pay for this. The federal government is going to have to get more and more involved ... there has to be more funding provided for treatment.”

That’s one reason why Bill Dunlap said the epidemic might grow to become a much bigger monster before it’s tamed.

Dunlap serves as the deputy director of the 317 Board, which coordinates and funds services for alcohol dependency, drug addiction and mental health in Athens, Hocking and Vinton counties. After working with the board for about two decades, his energy has been almost entirely devoted to combating opioid addiction by any financial means available for the past few years.

“It’s out there: People are addicted and they’re not getting into treatment,” Dunlap said. “We’re doing everything we can, but the system is not working at full-throttle as it should.”

Dunlap took a seat at the head of the table in the Hocking County Health Department in Logan on March 23 and tried to draw a path out of the opioid epidemic with a room of health professionals, counselors, addiction service providers, law enforcement and recovering addicts.

He’s been doing that for years. The motions are familiar now.

Hocking County’s opiate task force is where solutions typically start, Dunlap said. He has led the group in its monthly meetings since 2011, when the task force was established. Since then, a task force has also been developed in Athens.

Still, Hocking County’s task force remains the most active, Dunlap said.

The 317 Board’s opiate task forces promote awareness of the epidemic or drug-free alternative activities for local teenagers. Task force members have also researched which recovery and prevention models worked in their communities — such as trauma-informed care or wraparound treatment services that attempt to address an addict’s individual, unmet needs — all while manning the gates of the epidemic.

Dunlap told the room that the board will be throwing itself into complicated grant proposals to try and draw money to the region following the recent passage of the 21st Century Cures Act, through which Ohio expects to receive $26 million over a two-year period to fund programs that will address the opioid crisis.

That’s what Southeastern Ohio counties often grapple with most when trying to establish programs.

At that meeting in March, Hocking County Municipal Court Judge Fred Moses sat opposite from Dunlap, frustrated. The two men work closely together; Dunlap often attends Moses’ highly successful Vivitrol Drug Court each week.

It’s more than just money. Moses said the “little people” like those serving on their task force are going to be ignored while the culture of the epidemic still rages on — funding or not.

“The truth is, we can do all we want, we can cooperate all we want, but heroin is a byproduct,” Moses said. “It’s not the cause.

“Until people are ready to tell the medical community to quit giving out so many pain pills ... it’s going to keep going on,” he continued.

Ben Holter, pharmacy manager at Shrivers Pharmacy in Nelsonville, points to the Ohio Automated Rx Reporting System and its reports as one method of simply limiting the amount of prescription opioid painkillers being pumped into patients’ hands.

The program, often referred to as OARRS, collects information on prescriptions for controlled substances dispensed by Ohio-licensed pharmacists or personally furnished by prescribers. It’s something pharmacists can check before filling a prescription to see if it’s legitimate or to see if the patient has been doctor shopping.

Moses is the kind of judge who ditches the formal black robe for a button-down with rolled-up sleeves. He addresses everyone with a warm “how are we doing?” And his drug court is a space where recovering addicts can speak honestly to a judge who shares a bathroom with the public courthouse in a small town of about 7,000 people. When they graduate to another phase of their treatment, they’re awarded a neon-green shirt with “VIV” on its front.

Dunlap shows that shirt proudly, saying those in the program designed it themselves. The “VIV” stands for what they feel when they graduate: valor, integrity and victory.

There is a way out of addiction, Dunlap said. Moses’ drug court proves that.

Still, there’s much more that has to be done before the epidemic can begin to be considered curbed: reduce the level of opioids prescribed and in circulation, promote awareness and prevention from an early age and ensure a wide range of resources are available for those at-risk, such as mental health care or access to jobs.

“We’ve created this problem ourselves, and now we have to reel it in,” Dunlap said.

And there are many battles ahead for advocates yet, Dunlap said. The Ohio Association of County Behavioral Health Authorities, which represents the interests of groups such as the 317 Board at the state level, is looking to use federal funding for nine stabilization centers at $1 million each, $6 million for crisis centers and then $12 million to be dispersed to the boards to address the opioid epidemic within each of their respective communities for the state’s 2018-19 biennial budget.

And that funding will only begin to cover some of the area’s needs.

We’re not getting out of this epidemic anytime soon, O’Harra-Brown said, unless we ensure every individual addict is met with the level of care that any person with a diagnosed disease would have access to. As a nurse practitioner, she sees patients every day who desperately want access to addiction treatment.

A photo of her daughter floating in blue water hangs above her desk. It can be exhausting to tell the story of Hannah’s accidental overdose death again and again, she said.

Through the Athens County Sheriff’s Office Criminal Interdiction Unit, local law enforcement agencies have realized that opioid drug abusers should be offered recovery services instead of just jail time, Athens County Sheriff Rodney Smith said. The agency’s focus has been on stopping those who are trafficking or dealing drugs, and in educating the public on the dangers of the epidemic.

“We want people to know that we do see this as a medical issue, not as a criminal issue,” Smith said. “We want to reach out as much as we can and bring in as many resources as we can to these addicted people and let them know that they’ve got somebody they can call.”

Still, she has spoken to thousands of students through Hope Blooms, an organization founded by friends and family soon after her daughter’s death, to educate students about how quickly one can become addicted and that prescription drugs aren’t always necessarily safe, especially when combined with alcohol.

She stands before those students — about 650 at Lancaster High School when Hope Blooms visited in March — and shares that photo of her daughter, among others. She would rather be doing anything else in the world. It makes her cry. It’s painful.

“If it saves someone else from suffering from what my family suffered, I can make myself uncomfortable,” O’Harra-Brown said. “I can make myself sad. I can make myself do it.”

The students sit attentively and listen to O’Harra-Brown as she remembers Hannah’s life and describes her untimely death.

Some days, O’Harra-Brown said it feels like she’s banging her head against a wall. She questions her impact or whether society is getting any closer to slowing the epidemic of overdose deaths.

But others, students will approach her after she talks. They’re glad someone talked about it. Someone has to.

“It’s just like anything else, you just have to keep chipping away at it,” O’Harra-Brown said. “That’s really all you can do.”