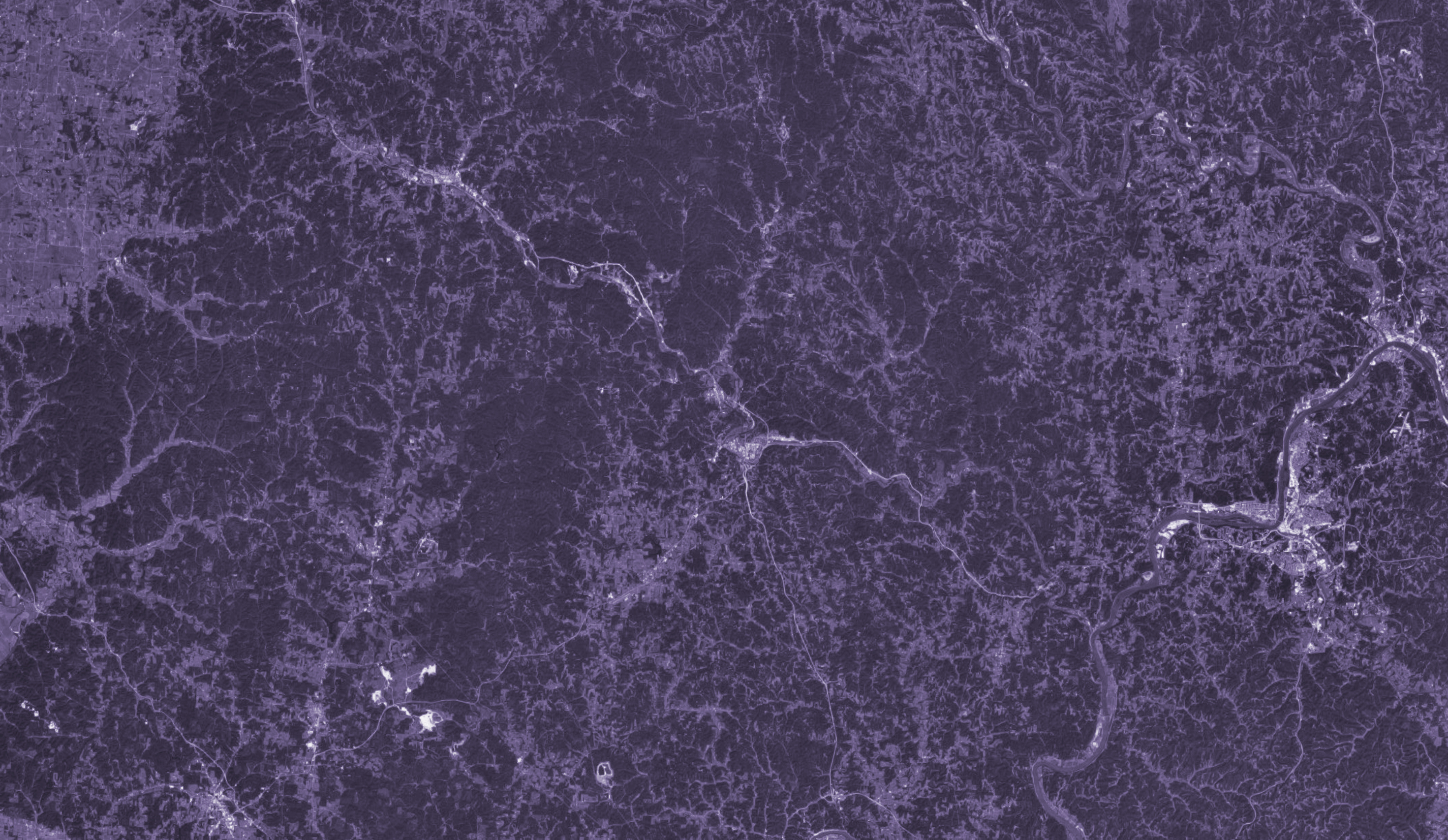

Satellite Image from Google Earth

Alex Meyer / Senior Writer

Though the opioid epidemic has not been unique to Appalachian communities, the effects of addiction might be more wide-sweeping in a region like southeast Ohio where resources are few and budgets are slim.

“It’s poverty, drug abuse and mental illness,” Bill Dunlap, deputy director of the 317 Board, which provides and funds mental health and addiction services for residents of Athens, Hocking and Vinton County, said. “Those are the three main problems that we see with people who are dealing with multiple barriers to move ahead.”

Dependency can be tied to the availability of jobs, Ron Eller, professor emeritus of history at the University of Kentucky, said, while drugs, alcohol and other substances can fill an economic gap for some people.

Scott Zielinski, director of the Athens County Department of Job and Family Services, said he and others at the department have seen an “alarming shift” in opioid addiction over the last six or seven years. But he stressed that services have been affected by opioids since the 1990s.

“When manufacturing and blue-collar jobs started leaving our area, we saw an increase in opiate abuse,” Zielinski said. “Unfortunately, at the same time, we saw federal and state decreases in investments in social services to help families deal with the issue.”

A closer look at the history of the Appalachian region as a whole reveals a trend of dependency stemming from economic or social determinants, though Eller stressed that people should not associate opioid abuse with the residents and culture of Appalachia. Rather, he said, one should look toward the broader factors that can lead a person to drug dependency.

For example, Appalachian counties have long witnessed economic exploitation and extraction of natural resources, which have resulted in economic inequality. That, of course, is of no fault to the people living in such communities.

“One has to look at the historical, economic and political conditions that have shaped life in the region today, not in the culture and attitudes in the people,” Eller, who has studied and written about Appalachian history and economic development, said.

Company mining towns, which once flourished in southeastern Ohio, gradually declined and took accompanying industries with them. The coal industry, for example, experienced a steady drop in production in the state after 1970, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

That left Appalachia with considerable poverty and a lack of opportunity, Eller said.

Notably, poverty rates have steadily increased in Appalachia in past decades, rising from 14 percent in 1980 to an average of 17.2 percent at the beginning of 2010, according to the Appalachian Regional Commission. Per capita income in the region was at about $37,000 in 2014 compared to the national average of about $46,000.

An average of 31 percent of Athens County residents were living in poverty in 2015, according to a report published in February by the Ohio Development Services Agency. The county’s economic status was also listed as "at risk" by the Appalachian Regional Commission for the 2017 fiscal year.

Out of that poor economic environment, Eller said, comes a tendency for people to turn to substances based on dependency, such as alcohol and tobacco, historically.

Coal mining, for example, is linked to admissions to substance abuse treatment centers for opioid abuse, according to a 2008 study published by the Appalachian Regional Commission. The study showed that coal mining areas in Appalachia demonstrated higher rates of heroin and opioid abuse as reasons for receiving treatment compared to other parts of the region.

Still, that does not mean that addiction can be cast as a choice made by those living in poverty to avoid confronting deeper problems.

“The conception that (some people are) giving is that these people are lazy, they won’t work — that’s not the truth in the vast majority of cases,” Reggie Robinson, program manager at Health Recovery Services in Athens, said. “Even the people in poverty, sometimes, self-blame. That’s not constructive.”

Those who are suffering from addiction in southeast Ohio might face additional barriers to recovery, such as a lack of transportation, additional health problems or basic skill deficiencies, Zielinski said.

The Department of Job and Family Services helps people work to overcome such obstacles, though he added that the prevalence of addiction can increase the difficulty in providing services to families.

“Low-income families without a safety net are hit especially hard when a family member becomes addicted,” Zielinski said. “It becomes even harder for low-income families to move forward.”