Landing Page

Special Projects

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.

SARAH OLIVIERI

11.08.17

Carla Triana wasn’t sure what she wanted to be when she grew up. She wasn’t aware of her possibilities. Before she moved to Wauseon, a predominantly white city in northwest Ohio, she had lived in Colonia, Hidalgo, Mexico, a small town with only five streets where the houses were made of concrete and everybody knew each other.

Her father went to the U.S. to work when she was 4 years old and would send money back to them. Triana, her mother and her younger sister lived in a small house without a bathroom and would take baths with a water-filled bucket. She would help her mother go door-to-door selling homemade empanadas.

“Society wants to put us in a box and label us.”– Carla Triana

After moving to the U.S. when she was 5, Triana ran sprints for her track team in middle school. She was actually pretty good, she said. But when she would race, her teammates would comment, “There’s the Mexican running away from immigration.”

While visiting family in Mexico, she didn’t entirely fit in. She felt like she couldn’t pronounce certain Spanish words correctly; in the U.S., she would make mistakes pronouncing English words.

“I’m stuck in the middle. I’m trying to find where I fit in,” Triana said. “Society wants to put us in a box and label us.”

Like Triana, other Latino students have experienced an identity crisis as they juggle fitting into two worlds — their world of comfort with their own culture and a world of white at their university. Some Latinos have experienced microaggressions, subtle or unintentional discrimination, and they try to find how to fit in a primarily white school.

Born in Mexico City and raised in Cincinnati, Gabriela Godinez-Feregrino would say she grew up “half and half.” Having moved to the U.S. when she was 2 years old, her family made sure it kept in touch with its heritage. She grew up speaking Spanish and visiting extended family in Mexico about twice a year. Godinez-Feregrino had a fun childhood, but she said it was hard.

“You’re never American enough, and you’re never Mexican enough,” Godinez-Feregrino said.

In the U.S., people would remind her she was Mexican and not fully American. Questions like “You’re Mexican, right?” and “Where are you really from?” would frequently roll off people’s tongues. And when Godinez-Feregrino would visit Mexico, her cousins’ friends would shrug her off, saying, “You’re just American, so you don’t get it.”

Godinez-Feregrino grew up in a bubble of immigrants in Cincinnati. The majority of her friends were also immigrants. Her best friend was a refugee from Burma, and she found they shared the same hardships, despite coming from opposite ends of the world.

She remembers one of the first times she ever explained to someone she wasn’t undocumented. When she was 10, she went to a Girl Scout event. She and her friends had been talking about visiting family during the holidays. A parent, confused, asked her how she was able to go back to Mexico. Godinez-Feregrino didn’t understand the question, but her mother jumped in and mentioned how they had just renewed their passports.

“Never did I ... allude to the fact that I could possibly be undocumented because that wasn’t true,” Godinez-Feregrino said. “It wasn’t even on my mind. I didn’t know people did that. I was 10.”

When Godinez-Feregrino became a citizen in seventh grade, she experienced a spiritual transition. Before, her mother had felt uncomfortable with singing the national anthem. But once they finally earned citizenship, the national anthem and the American flag intensified in her life.

“Now it is yours. Now, legally, it is yours,” her mother told her.

Once she became an American citizen, bullying also started. People would tell her “go home.” She could not understand how a piece of paper that legitimized her right to be in the country and meant so much to her, meant so little to anybody else.

“It was definitely a miniature crisis,” Godinez-Feregrino said. “I was also at the same time coming to terms with my sexuality, with being queer, like bi or pansexual, so it also wasn’t very healthful that my racial and my sexual identity were colliding at the same time.”

Her mother tried hard to keep prejudice away from her daughter. Looking back, Godinez-Feregrino remembers when they were shopping at a mall, and a manager wouldn’t leave their side. Godinez-Feregrino wondered why the manager had followed them, and later, would realize the manager thought they were going to steal.

“My whole world,” Godinez-Feregrino said. “Everything just shifted because I realized that my mom was so good at hiding it from me.”

delfin bautista, the director of Ohio University’s LGBT Center, was born and raised in a Spanish-speaking household in Miami, Florida. bautista, who uses they/them pronouns and the lowercase spelling of their name, didn’t realize how much of a minority Latinos are in certain areas, first when they went to graduate school in Connecticut and then when they came to OU’s campus.

People would tell them that they don’t look Latino. And bautista would ask, “What am I supposed to look like?”

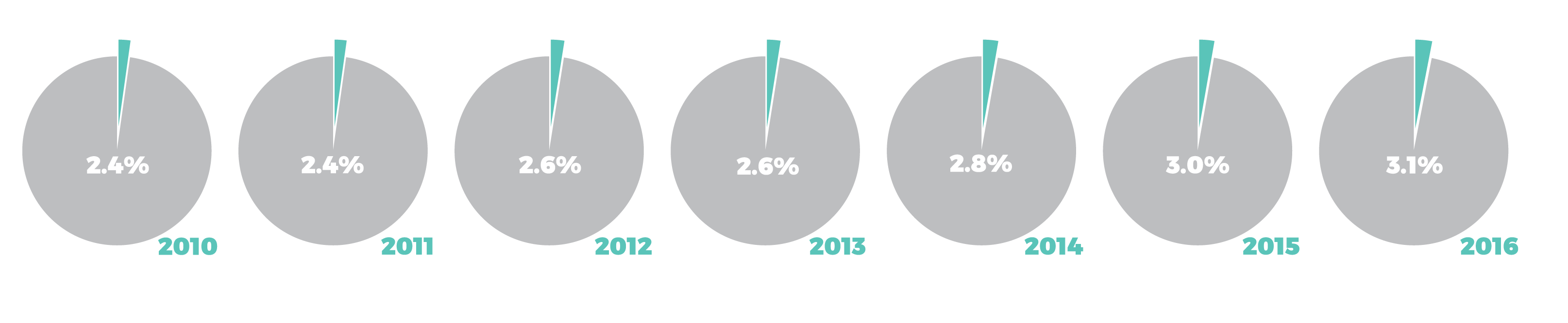

In 2016, Hispanic students made up 3.1 percent of the OU student body, compared to white students, who made up about 78.7 percent, according to the OU Factbook from the Office of Institutional Research.

Sarah Olivieri | ILLUSTRATION

“It’s just very lonely and isolating,” bautista said. “Where do you find community? And then, having to constantly justify and prove your Latin-ness.”

Triana remembers crying a lot. When she was 5, she and her mother and sister moved to the U.S. to meet her father. Her uncle drove them to a house, where they waited for coyotes, people who smuggle Latin Americans across the border. They stayed in the house for about a month, and crossed the border while hidden in vehicles on Thanksgiving in 2000.

Before gaining a green card through her family’s immigration lawyer, Svetlana Schreiber, and later her citizenship, Triana lived as an undocumented immigrant. Her grandparents died soon after she came to the U.S. Unable to return to Mexico, she never got to see them.

“I don’t have many memories of them,” she said, tears brimming in her eyes.

Living as an undocumented immigrant shaped her. She had to grow up fast, Triana said. At 7 or 8 years old, she was translating for her parents at banks and interviews — “big, grown-up stuff,” she said.

Triana would try to assimilate to her white friends’ culture and blend in. While she was proud, she also neglected her own heritage, as she couldn’t speak about it. She feels she has a divided identity that is split among two groups, sometimes referred to as the “1.5 Generation.”

Triana attributes her immigration status and her divided identity as one of the reasons why she has suffered from mental illness. It affected her academics, caused her to be a fifth-year senior and “infected” her relationships. Triana believes mental illness is a big problem in the Latino community — since religion is highly influential in Mexico, some people think they can just pray, and it will get better.

“Getting out of bed was difficult. Eating was difficult. Those were really hard times,” Triana said.

Gabriela Soto, an undecided freshman in the College of Arts and Sciences who is from Humacao, Puerto Rico, has felt very welcome at OU. Her first week, she made friends with people in her dorm and joined the Latino Student Union. When Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in September, her friends in the LSU comforted her.

“I feel like I have to be playing a game on a board that was not made for me”– Godinez-Feregrino

“I joined Latino Student Union because, even though I came here to explore new things, I knew that I was going to get homesick,” Soto said. “The Latino Student Union was the closest thing, I guess, to Puerto Rico.”

Godinez-Feregrino, a senior studying integrated media, however, felt like an outsider. Occasionally a classmate would say something underhandedly racist, and she wouldn’t feel comfortable standing up for herself, afraid her professor would take offense.

“I feel like I have to be playing a game on a board that was not made for me,” Godinez-Feregrino said.

Hispanics made up 17 percent of students (both undergraduate and graduate) enrolled in college in 2015, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. And as of 2012, the Hispanic college enrollment rate surpassed that of white students, according to Pew Research Center.

So, the number of Latino students at OU is pretty “shameful,” Alicia Chavira-Prado, the special assistant to the vice provost for Diversity and Leadership, said.

“We need to do better,” she said. “If we don’t respond to those demographics, we’re missing out. We need to grow as the nation’s trends grow.”

When Triana, president of International Student Union, came to OU as a freshman, she didn’t know any Latinos and considered transferring to Ohio State University for that reason.

“I don’t think lonely even describes it,” Triana said. “How the emotion, the feeling, desperate for people to look like you. ... I felt very unwelcome, like I didn’t really fit in.”

When Godinez-Feregrino was a freshman at OU, she had never experienced such physical isolation. In high school, if she experienced microaggressions, she could go home to her family — but in college, she was on her own.

Godinez-Feregrino toyed with the idea of a dorm for people of color, as it could be useful and make Latinx students feel safe and comfortable in their own space. Latinx is a term often used as a gender-neutral or non-binary way to refer a person of Latin American descent.

“But what are we going to do? Keep isolating ourselves? Keep segregating ourselves?” Godinez-Feregrino asked. “Having space for people that are of color, Latinx people where you can speak spanish and not get dirty looks is really nice, but that’s not how the world works.”

Programs and organizations like Latino Student Union exist, Godinez-Feregrino said, but those programs are not for her anymore because she is helping to organize and put them on.

“We’re all so tired,” she said. “Why is it our job to take care of ourselves … when it comes to visibility? That shouldn’t just be my job. That should be a university job to make other freshmen feel safer. Because honestly, I’m burning out.”

Godinez-Feregrino said it was also hard being intersectional, trying to fit in with both the LGBT community and the Latino community. SHADES, an LGBT group for people of color, has helped her a lot, and that’s where she’s made her best friends. Groups that focus on intersectionality are helpful, Godinez-Feregrino said.

OU works to promote diversity, but one area of growth is with Latinx students, faculty and staff, bautista, the adviser for the LSU, said. While recruiting and promoting diversity is crucial, it is equally important to not tokenize diversity, and genuinely care and celebrate Latino students. The university also should help create spaces where two or more identities can be recognized, bautista said.

“I think we are very quick to put people in boxes,” bautista said. “‘Here are the black students, here are the Latinx students, here are the gay students, here are the international students.’ But the reality is that those students are much more than that one box.

Additional funding to groups like SHADES and the Multicultural Center, Women’s Center and LGBT Center would help those organizations put on more events, Godinez-Feregrino said. Providing more diversity training and hiring more people who care about diversity can help Latino students, too.

“We may be few, but when we find each other, we really truly embrace,” Chavira-Prado said. “Our friendship, our camaraderie, and there’s lots of good people here that have sincere appreciation for multiculturalism, for minorities who are deeply committed to social justice.”

In February, Triana was one of 70 students arrested in Baker Center. She sat with the other students to protest national immigration policies, seeing a stark reality that if Schrieber, her immigration lawyer, hadn’t helped her family, she could have been one of the students in fear of deportation. Now, Triana has decided what she wants to be when she graduates: an immigration lawyer.

“I want to give other people the opportunity to pursue their dreams and goals and go to college, start their own business, without the fear of being deported,” Triana said. “I want to help change people’s lives. I want to be an advocate for immigration. That’s what I want to do.”