1996-1997: Wayne State College (Nebraska) (Assistant)

Record: 21-7 (.750)

Provided via the University of Wisconsin-Platteville

04.13.18

Saul Phillips still remembers it three years later: the moxie of freshman walk-on Sam Frayer, who approached him before practice one day in 2014 and asked a question Phillips hadn’t dared to broach when he’d been in the same position.

“Coach, do you think I’m ever going to play?”

Phillips, then in his first year at Ohio, turned to Frayer and delivered a decisive response: “If I do my job, no.”

It was an honest, easy response for Phillips to give because he knew what it was like to hear it from the other side. Some 20 years earlier, he had wondered the same thing as a backup guard at Division III Wisconsin-Platteville. He just hadn’t had the guts to go up to coach Bo Ryan to find out.

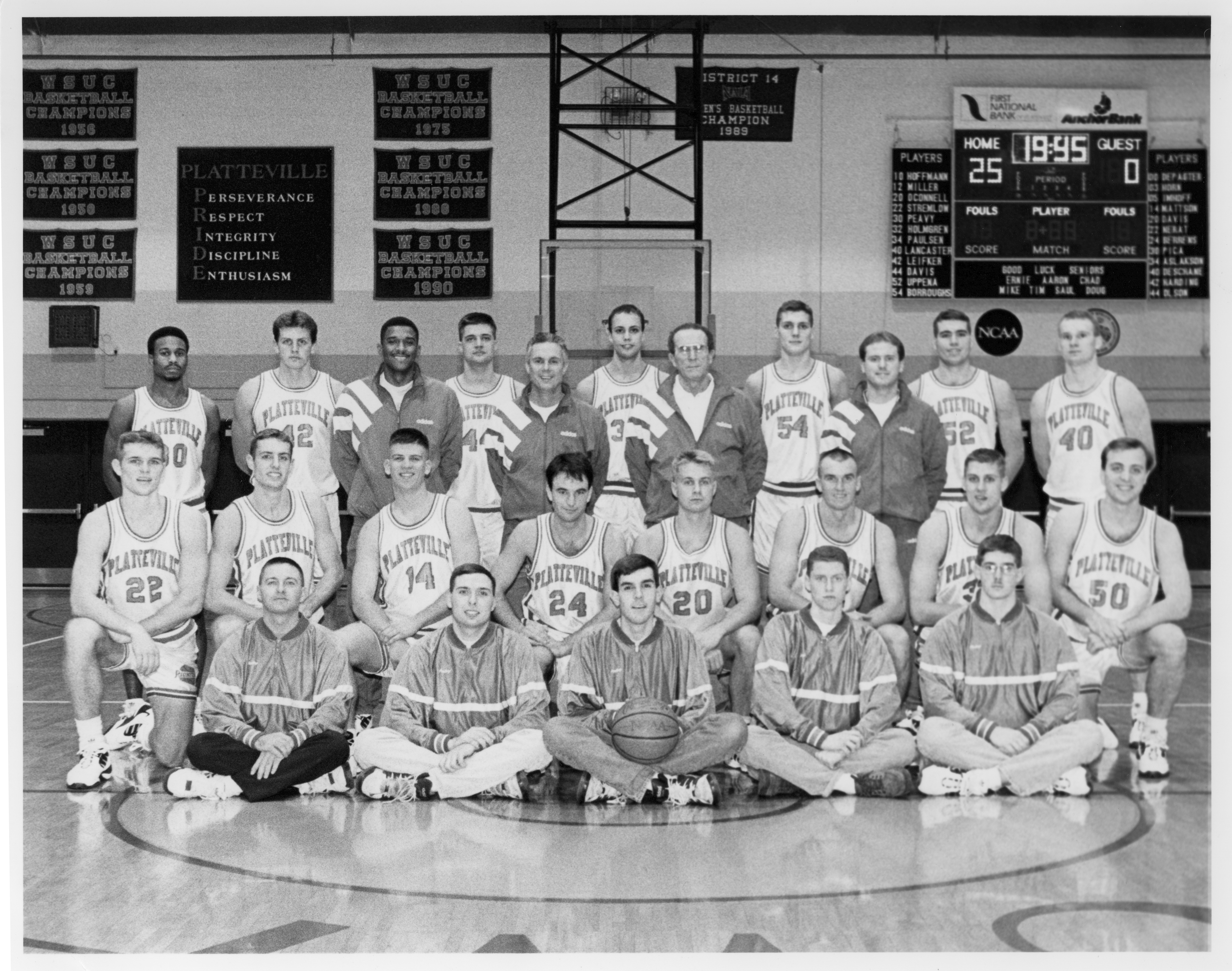

Provided via University of Wisconsin-Platteville

Phillips (24), seated in the middle row, poses for a team photo for the 1994-95 Platteville Pioneers.

Phillips still remembers what happened then, too. Squeezed into Ryan’s office, surrounded by stat sheets and towers of VHS tapes, he learned that Ryan was moving an All-American to his position.

“I knew what that meant for me,” Phillips says now, sitting in his office roughly twice the size of Ryan’s from that fateful day. “I knew I was never going to be a starter.”

He took the night to mull over his options. Basketball had felt like his lifeblood, but it no longer matched his input with output, as it had when he was a high school standout.

He could leave for the University of Wisconsin, where most of his family went, and live up two or three more years as a regular college kid at a big state school. There, he’d escape the dozens of games and hundreds of practices that had put shackles on a chunk of his free time.

Phillips, now the fourth-year men’s basketball coach at Ohio, pondered silently in his room. “What am I doing here?” he wondered. “What do I want to get done?”

By the end of the night, he had his answer. He was staying in Platteville. He’d long suspected basketball meant more to him than just on-court minutes. His decision to stay proved that.

“I didn’t come here to set the world on fire or revolutionize the game with my play,” Phillips says. “I came here to learn to be a coach.”

•Games played: 45 (no starts)

• Points: 25 (0.6 points/game)

• Shooting percentage: .250 (6-for-24)

• 3-point shooting percentage: .333 (3-for-9)

• Assists: 6

• Turnovers: 12

• Rebounds: 7

Within five minutes of meeting Phillips for the first time in 1991, Ryan knew the young player’s intention. They sat in Ryan’s office and talked about the potential of Phillips joining the Platteville basketball team. Under a thick mop of brown hair, Phillips couldn’t wipe the look of eagerness off his face.

“He said, ‘I plan on being a coach, and I want to learn from the best,’” Ryan recalls. “So I turned around to see if anybody was behind me. And there wasn’t so, my goodness, he was talking about me.”

Phillips came to Platteville by way of Reedsburg, Wisconsin, about a 90-minute drive upstate. He was an undersized, free-shooting guard who spent most of his waking hours playing or thinking about basketball. He played every day he could, often dragging buddies off their couches to join pick-up games.

“He said, ‘I plan on being a coach, and I want to learn from the best. So I turned around to see if anybody was behind me. And there wasn’t so, my goodness, he was talking about me.”Bo Ryan, Phillips' basketball coach at Wisconsin-Platteville

At Reedsburg High, he’d sneak into the gym in the morning and shoot until the principal threatened to call the cops. By his senior year, under a new principal, Phillips worked his way into 6 a.m. pick-up games with teachers and received a key to the school.

“It was funny, because my town wasn’t particularly basketball-crazy,” he says. “But I just lived it.”

Phillips often likes poking fun at people, and his favorite target is himself. He jokes that he only played D-III basketball because there wasn’t a D-IV.

“Look at my body,” he says now at 45. “I wasn’t meant to be a basketball player.”

No, Phillips never grew to 6 feet tall. And no, he wasn’t the quickest on the floor either. But he was a gamer. Basketball instilled obsessiveness in him.

His D-I passion, however, overmatched his D-III size and skillset. So he applied that obsessive attitude to becoming a basketball coach.

“I was extremely laser-focused just on basketball,” he says. “And I didn’t know how far it would take my playing career, but I knew if I wanted to coach in college, I needed to play in college, more than likely. So I was going to get good enough for that.”

Phillips did get good enough to play in college. And playing for Ryan’s Platteville Pioneers, who were coming off the 1991 D-III national championship, piqued his interest.

He makes it clear Ryan wasn’t pursuing him. A few loose connections to Ryan — including Phillips’ principal at Reedsburg, who had previously worked in Platteville — put Phillips’ name in the coach’s ear. Because D-III teams were allowed a bottomless bench, Ryan had no reason not to at least invite Phillips for a visit.

When they met, Phillips knew Platteville was where he needed to be. He couldn’t pinpoint exactly what it was about Ryan, though. There were no buzzwords or rah-rah moments in their conversation.

“If anything, he made it sound like it was going to be very difficult work, playing for him,” Phillips says. “And I was like, ‘Cool, let’s do it.’”

Basketballs bouncing thunderously. Sneakers squeaking incessantly. Barked orders from Ryan or one of his assistants. Those were the most frequent sounds heard in Williams Fieldhouse during a Platteville practice. None of the players dared to speak.

“It was spooky quiet, and it was unnerving for those who came in from the outside,” Phillips says. “It was straight work. And I loved it.”

Ryan overloaded his players with fundamentals: passing, catching, dribbling, defensive positioning, protecting the basketball. The philosophy was to excel at aspects that don’t take talent.

This gave Phillips, one of the less talented players on a team that beat pretty much everybody by 15, a way to compete every day. He likened the practices to factory shifts: You walked in, punched your timecard, put your head down for two or three hours of labor and punched your timecard again on the way out.

The cliche isn’t far-fetched for Phillips, who treated college basketball as a job at times. He wanted to help the team whatever way he could, but ultimately he was there to be Ryan’s apprentice.

For his first two years, Phillips ran point for Platteville’s “Futures team,” the cutesy nickname for junior varsity. Between games, the Futures worked to replicate schemes of the upcoming opponent. Scrimmages didn’t end until the first-stringers beat the Futures.

Sometimes, the Futures lost brutally and quickly. But when they jumped out to a lead, Phillips didn’t let up.

He commanded play like a general, unafraid to call out his teammates for a careless pass or weak box-out. Even when they were annoyed with Phillips, they saw his knowledge of the game shining through.

“You could see he had basketball coach written all over him,” says John Paulsen, who joined the Pioneers the same year as Phillips.

“I’ve seen him run through tables. He’s the kind of guy that, if he had no chance to get a ball, it was so far out of bounds, he would go and dive after it anyways. You were not going to outwork him.”Doug Landerman, a team manager and Saul’s roommate for five years

When the Futures were clicking, Phillips made life difficult for the first-stringers.

“What the f--- are you doing? We want to get out of here at some point,” teammates would say.

Phillips’ response? Guard me, then. Screw you.

“It seemed like anytime he was playing, he was 100 miles an hour,” says Mike Uppena, a fellow Future.

“I’ve seen him run through tables,” says Doug Landerman, a team manager and Saul’s roommate for five years. “He’s the kind of guy that, if he had no chance to get a ball, it was so far out of bounds, he would go and dive after it anyways. You were not going to outwork him.”

Teammates admired Phillips not only for his hustle but also his tendency to lighten the mood.

Playing for a perennial 25-win national contender is daunting. When Platteville started to feel like a pressure cooker, Phillips lifted the lid with a joke or gesture. If Ryan chewed out a player on the bench, Phillips might slide over, put his arm around the player and say, “I’ve never seen anybody get yelled at like that and didn’t even play.”

In 1995, as tension mounted a half-hour before the national championship game, Phillips, wearing only a jockstrap, did karate moves on a stool in the middle of the locker room.

When reminded of that story, Ryan burst out laughing — though he wouldn’t confirm or deny it. He knows that type of interaction is what earned Phillips the respect of his fellow Pioneers.

“The most important conversations taking place are the conversations in the locker room when the coaches aren’t around,” Ryan says. “For good teams, it’s always good stuff.”

For as hard as he worked in practice, Phillips made sure he factored in fun. He acted like a coach at times, sure, but he was still a 20-something college kid with papers to write and midterms to study for. There was a time to be the bench-warming player-coach; there was a time to be a teammate’s beer pong partner.

Phillips hosted team cookouts and was always in the mix when guys wanted to hang out. His presence pulled players closer to one another.

“We did need a guy like Saul,” Landerman says. “Maybe not on the court, but … he brought everyone together, kept us loose, kept us in a reality check, and we understood things better when he was around.”

The problem was, Phillips didn’t just want to be around — he wanted more time on the court.

And the Pioneers simply didn’t need him. He’d served his time on the sidelines for two years, but he expected more for himself as a junior when T.J. Van Wie, the incumbent point guard, graduated and left the position vacant.

Vacant, that is, until Ryan tapped All-American small forward Ernie Peavy to fill it.

Deep in his heart, Phillips knew he wasn’t destined for a star role at Platteville. But hearing it out loud from Ryan, in his cramped office that barely had enough room for both of them, was a reverberating reminder of Phillips’ college purpose.

“He basically was tutoring for basketball when he was there,” Saul’s father, Charlie, says.

From that day on, Phillips never expressed an inkling of irritancy about his minutes. Even as friends like Paulsen and Uppena advanced to larger roles on the team, no one had a sense that Phillips was displeased with his playing time.

“I think that was a smart move by him not to sit there and pout about his minutes,” Paulsen says. “And instead just take a great attitude toward it, because I’m sure Bo saw that.”

Ryan also saw how Phillips, once a hungry-eyed, floppy-haired freshman, was evolving into an intelligent basketball mind with genuine coaching potential. During games, Ryan would hear Phillips down the bench calling out what the other team was about to do.

“They’re going to run blue!”

“They’re running 13!”

“Watch out for X right here!”

Ryan has had plenty of players tell him they want to pursue coaching. Phillips was far from the first.

“But not everybody works at it and was as astute as he was in picking things up,” Ryan says.

In his junior and senior seasons, which Phillips witnessed mostly from the bench, the Pioneers outscored opponents by 19 points a game. They stormed to a perfect 31-0 national championship in 1995.

In its dominance, Platteville looked like a quintet of surgeons, making fundamental passes and screens with precision.

“I had friends that stopped coming to games because they said it’s not exciting,” Phillips says. “What the hell am I supposed to say to that? They’d say, ‘Well, we know you’re going win by 20.’”

No matter. The 2,300-seat Williams Fieldhouse filled to capacity most nights. It was a glorified high school gym, equipped with royal blue bleachers that pulled out from the sides and brought front-row fans close enough to reach out and touch the inbounder.

The few thousand fans who weren’t jaded by 20-point wins were sometimes rewarded with cameo appearances from Phillips.

He’d grown to be a crowd favorite due to his visibility around campus — hanging out in the student union, zipping over hills in his black-and-purple Honda Spree scooter — and he relished the mop-up role in blowout games.

Phillips coined himself the “human victory cigar,” boasting that Platteville won every game he ever played in. That’s a 45-0 record, in which he scored a grand total of 25 points.

Once, in a game well out of reach, the Platteville crowd chanted, “We want Saul! We want Saul!”

Ryan, flashing his dry humor, walked down the bench to Phillips and said, “Saul, why don’t you go on into the stands and see what they want?”

When Phillips let go of playing time frustrations, he focused on having fun. Winning, as it turns out, is a whole lot of fun.

He’ll always have that national championship, regardless of how much time he spent on the court playing for it. But Phillips will also never forget what happened just weeks after the title, when tragedy struck and he needed to unite the team again.

On the Thursday before Easter, Phillips and some buddies went to a local bar for 25-cent beer night. At 6:30 Friday morning, Phillips’ house phone rang.

Something about the call felt troublesome. Who calls at that hour after quarter beer night?

“Salty, this is coach,” Ryan said on the other end of the line. “You’ve got to get in here. There’s no easy way for me to put this: Gabe’s dead, and you’ve got to help me tell all his teammates before they find out in class.”

Gabe Miller, who played in all 31 games of the perfect season, had died overnight from an enlarged aorta rupture. Before Saul had time to grieve, he hurried to Williams Fieldhouse and helped the coaches call players in one by one to break the news.

Phillips hems and haws over whether he was officially a captain at Platteville, given that he only met with referees at half-court before some of the games. But his leadership that Friday morning demonstrated more than he ever could have on the court.

He was the player Ryan called on to deliver devastating news to the rest of the team, in the same way a coach would. Phillips understood his teammates and how to get through to each of them.

“I think Bo would probably fully admit he’s fortunate to have (had) a guy like Saul that was kind of a glue for all those different personalities,” Landerman says.

With his playing career behind him, Phillips shifted to a one-year student assistantship under Ryan while finishing his five-year track to a business and psychology degree.

After that?

He hadn’t mapped out much of a plan.

“I was cocky enough to think that I was just going to get a job,” Phillips says.

It was college basketball coach or bust. He’d turned down his dad’s offer to take over the third-generation family business, a hardware store called Phillips DO It Center. He needed an internship to complete his business degree, but instead of vying for something with a Fortune 500 company, he went to Disney World and sold action photos at Splash Mountain.

Fully expecting to grab a coaching job after graduation, Phillips picked Disney World to maximize fun on his placement. For a summer, he lived among 4,000 college kids in a poolside condo in Florida, where the female-to-male ratio was 3-to-1.

“It was spring break for three months,” he says.

If Phillips was looking for a coaching job out of college today, having Ryan on his resume would be enough of a boon to shun all fallbacks and breeze through a summer placement with Disney.

But in 1996, Bo Ryan — a 2017 College Basketball Hall of Fame inductee, with four D-III national championships, a pair of D-I Final Four appearances and a .762 career win percentage — wasn’t exactly Bo Ryan.

“I’ve been lucky the whole way,” says Phillips, who started as a graduate assistant at D-II Wayne State (NE) in 1996 and became a D-I head coach just 10 years later.

What Ryan gave Phillips was a foundation for coaching, layered with fundamentals and cemented with discipline.

As the years passed and Ryan’s success grew, he brought Phillips along for the ride — first to Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where Phillips was an assistant for two years, and then to Wisconsin, where he was the director of basketball operations for three more.

His learning didn’t stop in Platteville: Phillips continued watching Ryan closely, particularly in the years the two spent alongside each other.

In 2001, the duo’s first year with Wisconsin, Phillips kept a journal for when something noteworthy happened in the program or Ryan faced a difficult decision.

X’s and O’s were sparse on the pages. Instead, Phillips scribbled about how Ryan dealt with a team that wasn’t gelling, how he handled players who played heavy minutes but were light on confidence, how he worked with a player who’d tried to commit suicide.

“(The notebook) probably focused more on trying to put my mind around what made (Ryan) special,” Phillips says. “What made him successful year after year after year. I was in there, I was part of it and I still can’t conclusively say, ‘This was it. That was it.’ But I do go back and look at it every once in awhile. Now it’s just a fun memory.”

One of Phillips’ most fun memories as a coach came just after a much more forgettable one.

On a Thursday in mid-January 2006, North Dakota State lost by two points at Utah Valley State. Phillips was an assistant coach for North Dakota State then, thanks in part to a recommendation from Ryan.

Two nights later, the Bison were in Wisconsin to face Ryan’s No. 13-ranked Badgers. Because Phillips would be in town, Ryan had organized a Platteville team reunion after the game at the nearby Nakoma Country Club.

Phillips was restless the night before the game and had a nightmare that his team failed to score any points. He awoke in a cold sweat.

The next afternoon — 40 hours removed from a loss two time zones away — North Dakota State beat Wisconsin by seven. To top it off, the Bison had started four freshmen.

“I’m thinking everyone’s going to be happy for me,” Phillips says of what was a hallmark win for North Dakota State during its transition to D-I. “And all my teammates are pissed off, because they knew that Bo could be in a pretty bad mood.”

What followed was a surprisingly pleasant team reunion despite an air of awkwardness. Ryan kept the focus of the event on the Pioneers.

The night was doubly sweet for Phillips, as he reconnected with old pals and reveled in the first major upset win of his career — against his mentor, no less.

“It was kind of like beating your dad in the driveway for the first time, where you realize, ‘Wait a minute, I might be OK at this,’” Phillips says.

Record: 21-7 (.750)

Record: Unavailable

Record: 52-41 (.559)

Record: 68-28 (.708)

Record: 52-32 (.619)

Record: 134-83 (.615)

Record: 67-60 (.528)

Role reversal can be a funny thing. This past August, when Ryan visited Ohio, he watched Phillips run his very own practice for the first time.

What stuck out to Ryan right away was the energy and intensity of Sam Frayer — the walk-on who, three years prior, had asked Phillips if he’d ever play.

“One of the first things out of his mouth is, ‘That kid’s your MVP right there! He just keeps the energy going all practice.’” Phillips recalls Ryan saying. “And I don’t think Sam even broke a sweat that practice, but he’s on the sideline talking and clapping.”

In Frayer, Ryan saw what he used to see in Phillips. Frayer, a crowd favorite who recently wrapped up his career with 36 games played (zero starts), spent more time at practice teaching than dribbling. His smile is infectious. His laugh is, too.

Frayer also yearns to coach. His journey through his playing career, swapping minutes for methodology, mirrors the path Phillips took.

Who better for Frayer to learn from than a coach who tackled the same sacrifices and has since found success?

“I’m safe to say this is the best place to be a walk-on at because of our coach,” Frayer says.

Phillips knows a team is at its best when all players are engaged. He remembers the sweat, fatigue and floor burns he endured for the Platteville Futures to force the first-stringers to work hard.

He rewards his bench the same way he’d been rewarded: subbing them in as human victory cigars when games are comfortably in hand.

In an 80-37 win this past December, Phillips put in each of his players for at least seven minutes. When he has opportunities to make his bench players feel important, he does.

“I relate well to those guys,” Phillips said in the post game press conference. “Because I am one — was one. That’s why I never sit on the bench during the game. I sat enough when I played.”

He paused. Not satisfied that his joke had landed, he continued.

“Coach Ryan had the shackles on me.”

Finally, he looked directly into the camera trained on him in the press conference: “I could’ve been a monster, Coach, if you’re watching out there. Just kidding. It went OK.”

Landing Page

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.