Landing Page

Special Projects

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.

HANNAH SCHROEDER

10.05.17

At a 10 a.m. breakfast in Rye, New York, ahead of Ohio’s afternoon game last December against Iona, basketball coach Saul Phillips introduced Walter Luckett Jr. as a special guest to Bobcat players and coaches.

Luckett, 63, was dressed business casual as he often is, in a navy blazer over a light blue collared shirt and tan pants. He had a thin mustache, black glasses and trim dark hair that had barely thinned atop his head. He sat at one of four round tables with beige tablecloths filling a Courtyard Marriott conference room, which also featured a projector and blown-up photos of the 11 opposing players for a team strategy session after the meal.

Seated on his right was Phillips, who was meeting Luckett for the first time but had spoken to him on the phone regularly since earning the job at Ohio in 2014. Luckett was a donor and Bobcat super fan, but more importantly he was one of the greatest to ever put on the green-and-white uniform.

Some of Phillips’ players didn’t know who Luckett was, while others had only seen him on the cover of an old Sports Illustrated, encased safely in mint condition inside a plastic sheet that Phillips sometimes kept on the coffee table in his office.

When plastic plates and coffee cups had been pushed aside in New York, everyone focused on Luckett. He spoke to the team for 15 minutes that morning, telling a story — his story — none of the players knew, and one they’ll probably never forget.

“I mean, I’d heard about him,” Ohio shooting guard Jordan Dartis said months later at The Convocation, where Luckett had astonished thousands in his college days. Dartis looked up to the rafters and pointed to a green banner with a white (#34) on it. “He is up there.”

Dartis was honored to meet Luckett, but, like the others on the team, he didn’t really understand who the guy was beyond a name and number from yesteryear. Luckett wants to be remembered as more than just a basketball player. The magazine cover and retired college number are parts of who he is, but he won’t let them consume his legacy.

What happened to his basketball career — or what didn’t happen, depending on your perspective — stirs sympathy in those who hear the tale. As for Luckett, he’s plenty proud of what he did on the court, as well as what he’s done since walking off it.

“I’ll be honest with you,” he said, “I’m not a sad story.”

When Luckett was 8, his first love was baseball. His father, Walter Sr., coached Little League in Luckett’s hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and watched as Luckett and his three younger brothers thrived in the sport. To Walter Sr., sports — with their sets of rules and responsibilities, especially in team settings — provided discipline and structure for his boys.

So when a family friend told him about George Fasolo, the director and basketball coach at the Cardinal Shehan Center, Walter Sr. took Luckett there. At that rec center, Luckett found his true love: basketball.

At 12, he started playing in an after-school league on a team coached by Fasolo, who taught him the fundamentals. The practices, held three or four times a week, centered on running and passing, not shooting. Boys on the team wore jackets and ties for road games. They faced high school freshmen teams, which prepared Luckett to make the jump to varsity as soon as he entered 9th grade.

Fasolo, who idolized Vince Lombardi’s coaching style, taught Luckett about professionalism and accountability. If you weren’t on time, you didn’t play — period. No fighting, either, regardless what the other team or kids on the street were doing. And if anyone’s grades slipped, Fasolo would know, because he checked in with the parents.

Luckett was a good rebounder, and that’s what Fasolo wanted him to focus on.

“If you want to shoot, then you can stay here after and practice your shooting,” Fasolo would say. “But right now, we have to go do our drills.”

Luckett wanted to do more than grab rebounds, which meant staying late at the center and shooting on his own time. In the offseason, he took 1,000 shots every night. He led his team in scoring the next year.

So Luckett kept shooting, a thousand a night, all the way through high school. He counted his shots to make sure.

“It sounds creepy, I know,” Luckett said, laughing. “But I did.”

He practically lived at the rec center. In the summer, he was a camp counselor and had a job shellacking the court’s wooden surface.

“I knew every spot on this floor,” he said.

On that floor, Luckett crafted his jump shot: a left-handed, high-arcing fadeaway that was nearly impossible to block.

He’d pull the ball behind his head, almost far enough to hit himself in the back, and raise his left elbow into the defender’s face. Then he’d rise, flick his wrist with an effortless release and watch the ball rotate high above the backboard and perfectly into the hoop.

A thousand of those. Every night. For more than five years.

Luckett’s first big splash came his sophomore year at Kolbe High School, an all-boys Catholic private school of about 300 students, when he dropped 53 points against Abbott Tech. Luckett had just three points in the game’s first eight minutes, and one of his shots was swatted out of bounds. But in the second half, he filled the net and led his team to victory. Later that season, his coach referred to Kolbe’s other four starters as the “Forgotten Four.”

Provided via The Hartford Courant

Walter Luckett, (# 32), as a senior at Kolbe Cathedral High School.

Kolbe made the state tournament that season, and college letters started arriving at the family apartment. In Luckett’s junior year, his team won the state championship. His legend grew, as did the pile of scholarship offers. He read every letter and filed them away in boxes.

“No exaggeration, I heard from every school in the country,” Luckett said. “It was so many letters, it was ridiculous.”

That’s when the wheels started to turn, and he realized basketball could be more than a hobby. He was an honors student who loved business and economics and read The Wall Street Journal. Through basketball, Luckett envisioned a free education.

His high school games became must-see events in Bridgeport. People wanted to watch the tall, lean-muscled kid with the Afro who could score from anywhere inside half court. His favorite shot was from the corner, where he rainbowed the ball over defenders as his momentum pulled him out of bounds.

Luckett’s 2,691 career points, set in 1972, is still Connecticut’s high school state record. His light blue Kolbe jersey with golden letters is in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, along with a picture of him scoring the record-setting basket and his Sports Illustrated cover issue.

As a senior, he averaged 39.5 points, 16 rebounds and 13 assists a game and consistently played in front of capacity crowds. Road games were often held at university gyms to accommodate.

College basketball royalty came to town, including Indiana’s Bobby Knight, North Carolina’s Dean Smith and Maryland’s Lefty Driesell. Eventually, a section of Luckett’s childhood rec center, where Kolbe played its home games, was reserved for college coaches.

Luckett received so many letters and so much local attention, but the spotlight burned brightest when he was named the 1971-72 national high school player of the year. He had a decision to make: Where would he play his college ball?

He was going to be part of the first college freshmen class allowed to play varsity right away. That was before the era of one-and-dones, when star players barely walk on campus before leaving for the pros.

He’d have both an immediate and long-term impact on the school he picked. His choice mattered.

Ohio University assistant coach Dale Bandy picked up his office phone. It was an alumnus, Dr. Peter Yanity, who called about a high school kid in Bridgeport who was “out of this world.”

Luckett was just a sophomore at the time, but Yanity, a Connecticut dentist who was close with Fasolo, had watched him play since his elementary school days. Now Yanity was making the pitch to Luckett to attend his alma mater.

The two drove down to Athens, Ohio, for Luckett’s first college visit. When they drove into town, Luckett was immediately drawn to the 13,000-seat Convocation Center, which had opened two years before.

Provided via The Athens Messenger

“I just went nuts when I saw that,” he said. “It looked like the Madison Square Garden to me, in the Midwest.”

Upon meeting Ohio’s head coach, Jim Snyder, Luckett was impressed by his openness to talk about being a Christian.

“He didn’t do it because we were,” Luckett said. “It’s just the way he was. That made me feel very comfortable.”

Luckett also liked Ohio for its diverse student body and because it had the business administration program he was looking for. Becoming a Bobcat felt like the right fit. But other schools, namely Providence and North Carolina, offered enticing alternatives.

Providence had a promising team that made the NCAA Tournament in 1971, and the school was less than three miles from Brown University, where Luckett’s girlfriend, Valita, was headed.

North Carolina was coached by Dean Smith, whom Luckett admired. During recruitment, Smith had rolled up to Luckett’s home in a big, blue Cadillac and stayed for dinner.

Provided via Muncie Evening Press

Walter Luckett, No. 34, as a freshman at Ohio University.

Luckett consulted his parents and made his choice.

“My father discussed with me where I should go,” Luckett later told Sports Illustrated for its Nov. 27, 1972, cover story. “We thought about what many great players do — they go to be big fish in small ponds and I liked that.”

Providence and North Carolina, at least in basketball, were much more notable ponds. Ohio offered a grand arena to perform in, a trustworthy coach and an academic program Luckett wanted to pursue.

His decision left some people scratching their heads. But Luckett was, and still is, content with his choice.

“And I got the opportunity to see a lot of campuses and see what it’s like,” he said. “But I’m sorry, Ohio University was my first love, man. It just had everything I needed.”

As a high school senior, Luckett’s name and fame reached a new level.

Connecticut’s governor declared April 12, 1972, “Walter Luckett Day,” a statewide holiday. Luckett took the day off school and went to Hartford with his family, spent time with the governor and toured the state capital. He was about as close to rock star status as any Connecticut high schooler could be.

Yet he continued volunteering in his community as a fixture at youth basketball clinics who wouldn’t be changed by national attention.

Early that spring, Luckett was at a Bridgeport Elementary School demonstrating layups to youth players. He drove to the hoop and finished at the rim with ease.

Except one time, his momentum carried him under the net, and he banged his left knee off the metal radiator sticking out from the wall.

“Now, today, you’d put mats in front of those things,” Luckett said. “It was just a freak thing.”

His knee hurt like hell, but he got up. When the youth clinic was done, he walked home. He played in Kolbe’s early-round state tournament game two days later.

The Bridgeport Post, which chronicled almost every move Luckett made since he averaged more than 16.5 points a game as a freshman at Kolbe, called his knee “badly bruised” and reported he couldn’t bend it after receiving an injection.

Luckett missed one game. If he’d been able to bend his knee, he probably wouldn’t have missed any. The day after his knee injection, he was on crutches. Three days after that, he recorded 21 points and 18 rebounds in the state semi-finals.

Though Kolbe lost in the championship game, Luckett was unanimously named tournament MVP. To his surprise, the pain got worse. When he went for an X-ray, doctors found damaged cartilage that needed to be surgically removed.

The surgery was done poorly, but Luckett didn’t know that at the time. He could see the nine-inch scar running up his leg. He couldn’t see that the operation had turned his knee into a ticking time bomb that would take a few years to detonate.

The immediate problem was the recovery timeline.

His surgery was in early August, and doctors recommended a recovery time of six months to a year. Ohio’s season opener at Missouri was Nov. 25, which fell well short of appropriate rest Luckett needed. He went to Athens a month before classes started to begin rehabbing his knee.

Redshirting wasn’t an option in Luckett’s mind. He wanted to play and felt it was expected. He arrived with too much hype to sit on the bench. High school basketball scout Howard Garfinkel, who ran the Five-Star Basketball Camp — later attended by megastars like Michael Jordan and LeBron James — called Luckett “the best second (shooting) guard in the country” his senior year.

He was 18. The injury was a minor setback, one he planned to play through and move on from. Everyone at Ohio was counting on him to be the star he was said to be.

“You’re on the cover of Sports Illustrated — everybody saying you can do all these things,” he said. “So I think I kind of rushed it a little bit. But, you know, I was young.”

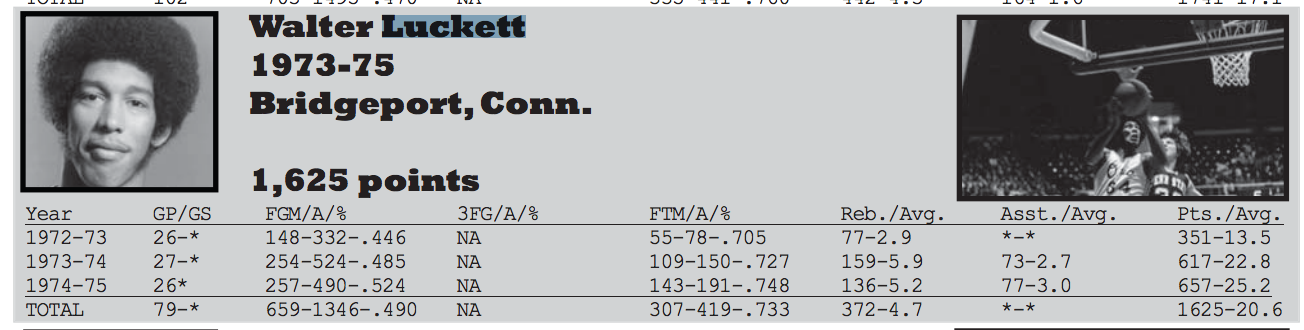

Provided via Ohio University Men's Basketball records

Sitting on the steps of Logan’s Bookstore on Court Street, Gary Binford heard the rumor that had been flying around campus. A fellow student told Binford that Walter Luckett was coming to Ohio.

“And I’m like, who the heck is Walter Luckett?” Binford recalls.

“Walter Luckett was show time, and people knew who Ohio University was because they had heard of Walter Luckett.”Gary Binford, an Ohio grad who covered the basketball team through Luckett’s career

Binford, an Ohio grad who covered the basketball team through Luckett’s career, soon had his answer. When Sports Illustrated came out with its 1972 college basketball preview, Athens was abuzz.

On the cover, Luckett was pictured in a semi-crouch at center court inside The Convo in his No. 34 Ohio jersey with wide eyes and a basketball, mid-dribble, in his left hand. He sported a trim Afro, green-striped tube socks up to his calves and a glaring white brace that started below his knee and ran up to his mid-thigh.

Today, people still mail copies of the magazine to Luckett’s home with attached postage so he can sign it and send it back. He always does.

In the fall of 1972, the magazine solidified Luckett as a rising star.

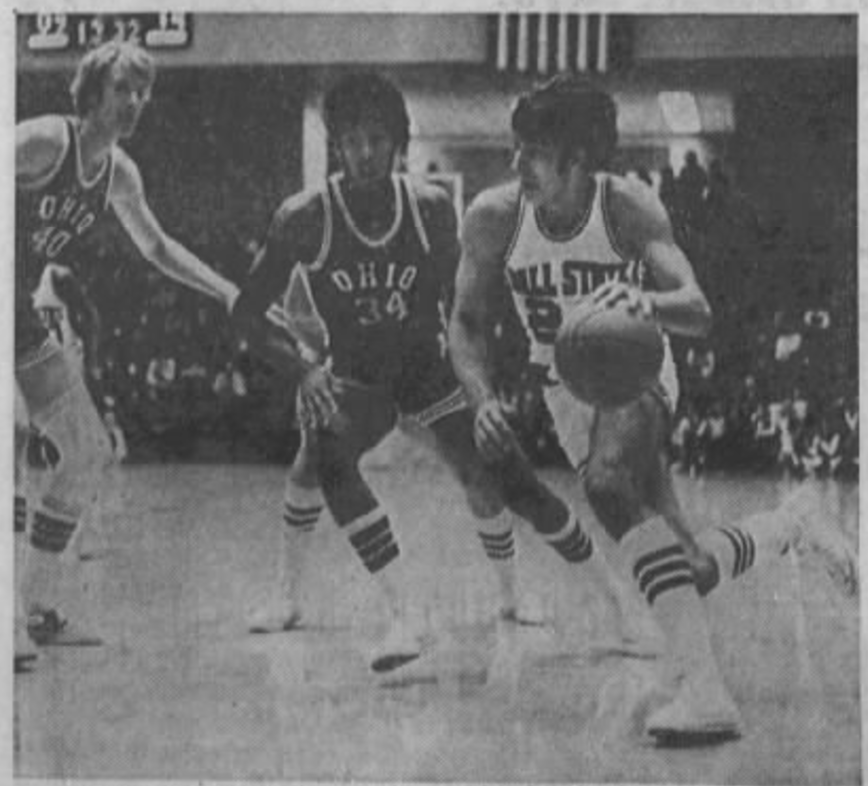

_%20February%2012_%201974.png)

Provided via The Daily Reporter

“Walter Luckett was show time,” said Binford, who is still friends with Luckett more than 40 years later. “And people knew who Ohio University was because they had heard of Walter Luckett.”

The Sports Illustrated story that went with the photo revealed a cool confidence Luckett had in spite of his injury. He told the writer, Curry Kirkpatrick, he’d score 15 points a game just by hanging around. Kirkpatrick called Luckett a “smooth, uncommonly mature swingman.”

Curiosity drove more than 10,000 fans to The Convo some games to see the “swingman” in person. The competition wanted to see him, too. Ohio hosted big-name teams such as Indiana and Wisconsin, and went on the road against John Wooden’s No. 1-ranked UCLA.

Luckett finished his Ohio career as a one-time conference player of the year and a three-time all-conference team member, while leading the Bobcats to an NCAA Tournament his sophomore season and scoring 20.6 points per game, the second-highest career average in school history.

Though he often had the ball in his hands when the game was on the line, Luckett played a complete game. He shared the ball and grabbed more than his fair share of rebounds, as he did in his earliest days playing back home. Fasolo must’ve been proud.

“If you were open, he’d hit you,” said Bill Brown, who played with Luckett at Ohio for a year and coached him for two years. “He had great vision and more importantly he could make tough shots and make it look easy.”

Making it look easy doesn’t mean it was. The knee problems lingered. Luckett’s injury slowed him down the first half of his freshman season, inhibiting him from even leaving his feet when taking shots. He played an average of 18-20 minutes per game and was held to four points or fewer four times. His lateral movements were his greatest weakness, shrinking his offensive arsenal and making him a defensive liability.

Provided via The Athens Messenger

He wore his knee brace and iced constantly before and after games to keep the swelling down. Though he missed a start here and there, Luckett didn’t sit out a single game in his time at Ohio.

“There were times when he may have fallen or came down the wrong way, and everybody would take a gasp,” Brown said. “But he got through it.”

Luckett’s scoring numbers soared the second half of his freshman season — by mid-February, he was jumping off one foot to shoot — and, by the start of his sophomore year, after spending the summer working out his knee at his father’s health spa, he appeared to be in full health.

In Ohio’s 1973-74 opener against Northwestern, Luckett scored 31 points and looked like the player everyone expected when he arrived the previous fall. He led fast breaks, drove to the basket and dropped shots from the corners.

“The guy, even after the knee surgery, was still one of the best players in the country,” Binford said.

After his sophomore season, Luckett was drafted by the San Antonio Spurs of the American Basketball Association. His sights, however, were on the NBA, so he turned the Spurs down. But it was a sign: Going pro was just a matter of time.

And yet, Luckett was a student at Ohio as much as he was an athlete. As a business major with a focus in economics, he spent much of his time off the court in study hall. Sure, he went to some parties. But he wasn’t a “bar guy.” When work had to be done, he got it done.

“He always had the foresight to look ahead and plan ahead,” Binford said. “I remember a lot of times he would have to go study because he had a legitimate major. He already understood basketball is a game.”

“Nobody loved the game more than I did,” Luckett said. “But you gotta have a Plan B.”

Luckett has no flashy story of how he met Valita, his wife of 43 years. A friend introduced them, and they began dating as high school seniors before heading off to colleges 700 miles apart.

They spent so many hours talking on the phone, Valita called home asking her parents to help pay her bill. Luckett proposed to Valita on a call their freshman year — she, of course, accepted — and surprised her with an engagement ring when she visited him.

By their junior year, the summer vacations and infrequent visits weren’t enough. Valita decided to transfer from Brown to Ohio so they could be together.

The move was surprisingly practical. Brown only offered economics, a more limited option than the general business program she found at Ohio. And her sister was nearby at Ohio Wesleyan University.

“I’ll be honest with you. I’m not a sad story.”Walter Luckett

Still, Valita’s decision meant leaving the Ivy League for a school in the rural Midwest.

“And thank God for that, because I’m very happy and very blessed,” Luckett said.

He spent as much free time as he could with Valita, taking her to The Downstairs restaurant on Fridays for $5 meals and to the Athena Cinema for midnight dollar movie nights to watch Bruce Lee films.

Valita drew Luckett’s bathwater before games, like his mother had done in high school, and she never missed a home game. She even rode with one of the sportswriters to a game in Chicago once, braving a blizzard for an eight-hour drive there and back.

At noon on Oct. 4, 1974, Luckett and Valita went to the Athens mayor’s office to be married. No friends, no family. Valita wore a blue dress with beige flowers and platform shoes. They didn’t take any pictures.

“I don’t regret it, to be honest with you,” Valita said. “I think Walter was such a superstar that if we had a wedding, it probably would’ve been more circus-like than ceremonial.”

The newlyweds asked the mayor to keep word of their wedding confidential, at least until they could plan a larger celebration. But by the time they were back at their apartment, the news of Walter Luckett’s marriage was already on the radio.

Coming off a losing junior season in which two players transferred, Luckett filed for hardship status to enter the NBA draft a year early.

Provided via The Athens Messenger

The decision to leave Ohio made sense given he was the leading scorer in his conference that year and his knee injury wasn’t causing as much grief as it used to. The hardship rule was less about players dealing with financial hardship than it was about players who were ready to go pro before graduation.

“I knew I was always going to get a degree, so that wasn’t a concern for me,” Luckett said. “I just wanted to make sure that my marketability would allow me to just get an opportunity in the draft.”

In May 1975, after Luckett’s request had been approved, he and Valita stood on their apartment balcony waiting for the phone. It rang. The Detroit Pistons had drafted Luckett 27th overall.

NBA drafting and scouting was much different back then. The draft was 10 rounds long instead of two. As for scouting, Luckett said coaches weren’t even allowed to reach out to players.

The league held no combines, psychology tests, physical tests or pro days as teams do today. It’s possible the Pistons had no clue about Luckett’s knee injury.

“Obviously, a guy averages that much in college, you figure he doesn’t have a knee problem,” said John Mengelt, a 10-year NBA veteran who played for the Pistons from 1972-76.

Luckett missed rookie camp because he was in contract negotiations, but he signed a three-year deal in time to go to veterans’ camp in Michigan. Finally, his dream of pro basketball had come to fruition.

Then his knee quit on him.

“I don’t know what happened,” Luckett said. “But the knee just blew up and withered away.”

The NBA practices were more intense than his college practices. Luckett was not a man among boys in Detroit as he’d been in Athens. Detroit coach Ray Scott held laborious workouts of dribbling drills and scrimmages that wreaked havoc on Luckett’s crumbling cartilage.

Provided via The Detroit Free Press

“The longer practice went, the more of a struggle it was,” said Mike Abdenour, a former Pistons trainer and current director of team operations.

Luckett’s knee filled with fluid. It was painful. It was stiff. It slowed him down. His lateral movements on defense were as challenging as they’d ever been.

From three full seasons of Division I college hoops, the cartilage damage had developed into arthritis. There was simply no strength left in his knee.

The inability to play how he wanted left Luckett frustrated. He was like a sports car with flat tires.

“If anybody had a body that just played no favors to its owner, Walter Luckett owned it,” Abdenour said. “His poor body would just not let him accomplish the dream that he so desperately wanted to aspire to.”

When Luckett didn’t make the team, he went back home to work on his business management degree at the University of Bridgeport. He regained enough strength in his knee to average more than 27.2 points per game in the semi-pro Eastern Basketball League, a feeder to the NBA.

He went to Pistons rookie camp the next year for another tryout. Once again, he couldn’t keep up physically because of his knee.

The mental pain was as bad as the physical pain. Luckett prayed constantly as he struggled with the reality of the situation.

“I didn’t have an NBA knee, and I knew it,” Luckett said. “I gave it a shot, man. But I was done with my leg. And it’s hard to believe after all the potential, but you know, God had another plan, I guess.”

Luckett played one more year in the Eastern League, earned his degree, then gave up the game for good and started his business career.

“That dream that he had, I’m sure it’s evaporated to the point where it’s a distant memory,” Abdenour said. “But part of that is what drives him every day. And that’s why he is the success that he is right now.”

Luckett’s first job after graduation was at Condec Corp. in Old Greenwich, Connecticut, as the head planner for the construction of military cannons.

He and Valita, who left Athens with Luckett and also finished her degree at Bridgeport, lived in New Haven, Connecticut. Luckett’s morning commute was a 45-minute train ride to Stamford and a half-hour walk to Old Greenwich.

After a couple years, Luckett joined Unilever (called Chesebrough-Ponds Manufacturing Co. at the time), which is the world’s largest consumer goods company today with brands such as Vaseline, Axe and Dove.

He started as an inventory analyst for health and beauty products. Later, he became head of customer service for North America, and then head of North America’s community relations and corporate contributions.

Provided via Valita Luckett

Walter Luckett with friend, Gary Binford, who covered the basketball team through Luckett's career.

Shortly after Luckett left basketball, a reporter came to his office at Unilever, hoping he’d be someone he wasn’t. The reporter wanted to tell a sad story. Perhaps of someone who’d fallen far from his potential and was forced to settle in life, or someone who never let go of the mental burden of a career-ending injury.

Instead, he saw Luckett in a big office, with awards lining the wall, at a Fortune 500 company.

“Sometimes, I think people expect you to be down and out,” Luckett said. “That’s not the case here.”

He retired in 2006. Now, serving communities across Connecticut is his full-time job.

Luckett has his own foundation, the Walter Luckett Jr. Foundation, which reaches more than 3,000 students aged 8-18 in seven Connecticut cities.

One of the programs he’s most proud of is SAT/ACT training, but he also sponsors summer basketball camps and programs that combine basketball with self-esteem training and team-building exercises.

He works with the Justice Education Center, a nonprofit corporation striving to strengthen communities in the state. Sherry Haller, the center’s executive director, met Luckett more than a decade ago, and they’ve worked together since.

Luckett and Haller work closely on a program called ECHO — an acronym for empathy, character, hope and opportunity — that trains students in self-esteem, leadership, health and wellness.

A branch of ECHO, called Perfect 10, is a program focused on teaching workplace etiquette and preparing students for an internship in corporate America. Luckett has 22 business partners he works with, including Unilever, AT&T, State Farm, People’s United Bank and local hospitals.

Juliemar Ortiz, one of the first students to cycle through ECHO Perfect 10 back in 2009, still remembers the nerves from her internship interview with Luckett and Valita.

Ortiz came from a single-income household in Bridgeport, a diverse city she described as “very hood,” where the poverty rate is 6 ½ points higher than the national average. Opportunities for 11th-graders to intern at local banks were unheard of.

She met Luckett when volunteering at a basketball camp he sponsored and knew of him as a successful businessman and community leader.

Only later, well after starting her internship, was she shown a very different version of Luckett.

“People are like, ‘Oh, this is him on the front cover of some magazine. Look at him when he was in high school with his ‘fro,’” Ortiz said. “And I’m like, ‘Oh my God, that’s Walter Luckett! That’s crazy.’ It’s really weird to see this guy had a whole other life before this.”

Ask Luckett what he misses most about that other life, and he’ll tell you: the fans.

He misses the rush of Saturdays spent performing on The Convo’s grand stage in front of thousands, when the court belonged to him.

Now, as an alumnus and donor, he watches on national broadcasts as the current Bobcats take their claim to the court. He can’t help feeling a little slighted when they score behind the 3-point line, something he would’ve benefitted from had it been part of the game in his day.

And though he’s out of basketball as a player, he remains a junkie for the sport on TV.

Reclining in front of his 70-inch screen, often with a bowl of strawberries or fruit salad, is a nightly activity. He prefers to watch the best teams, like the Spurs and the Golden State Warriors, and has little patience for high turnover rates and low scoring.

It’s hard to say what Luckett thinks about as he watches the Bobcats play where he played, or the Spurs and Warriors play where he didn’t.

As a teenager, Luckett didn’t stop long enough to recover from his injury. And maybe he should’ve, he’ll admit. Maybe, instead of a new life direction, all he would’ve been left with was the long scar on his leg. But worrying about what ifs never did anyone any good, he said.

“I’ve sat there and thought about what it could’ve been, but he really doesn’t think that way,” Binford said. “Because that’s what makes you bitter. That’s what makes you think you’ve been robbed.”

Luckett doesn’t like to think or talk about being robbed. He’s at peace with basketball and the role it has had in his life.

“That’s why I have no regrets — because I know I could ball,” he said.

When Plan A failed, he made the most of Plan B. You won’t hear Luckett complain because, in the end, it all worked out. He’s been places and done things in basketball that most can only dream about. No injury can take that away.

“I’m living the American dream.”

HANNAH SCHROEDER

Landing Page

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.