Landing Page

Special Projects

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.

Marcus Pavilonis

11.15.17

Editor’s note: The story’s version has been updated with additional information.

Dave Jamerson is fascinated by the professional athlete who longs for more.

He quotes articles about Tom Brady’s disillusionment after winning his third Super Bowl. He can quote scenes from Chariots of Fire, the movie about a runner who struggles to find purpose beyond the track and the documentary on former NFL quarterback Todd Marinovich.

As a former professional athlete, he experienced similar heights to Brady. He never won a championship, but he did achieve a life-long dream of playing in the NBA. He struggled to find his purpose away from sports just as Harold Abrahams does in Chariots of Fire. He lost his way when he wasn’t feeling fulfilled, just like Marinovich.

At one point, Jamerson, 50, picked the wrong God, but he found his way out.

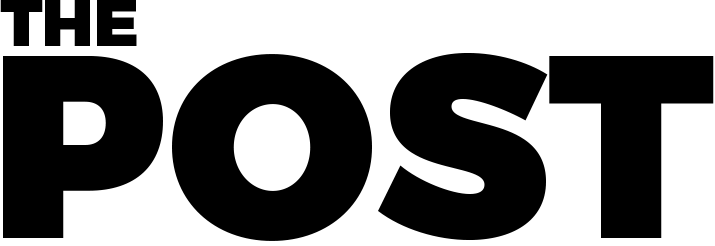

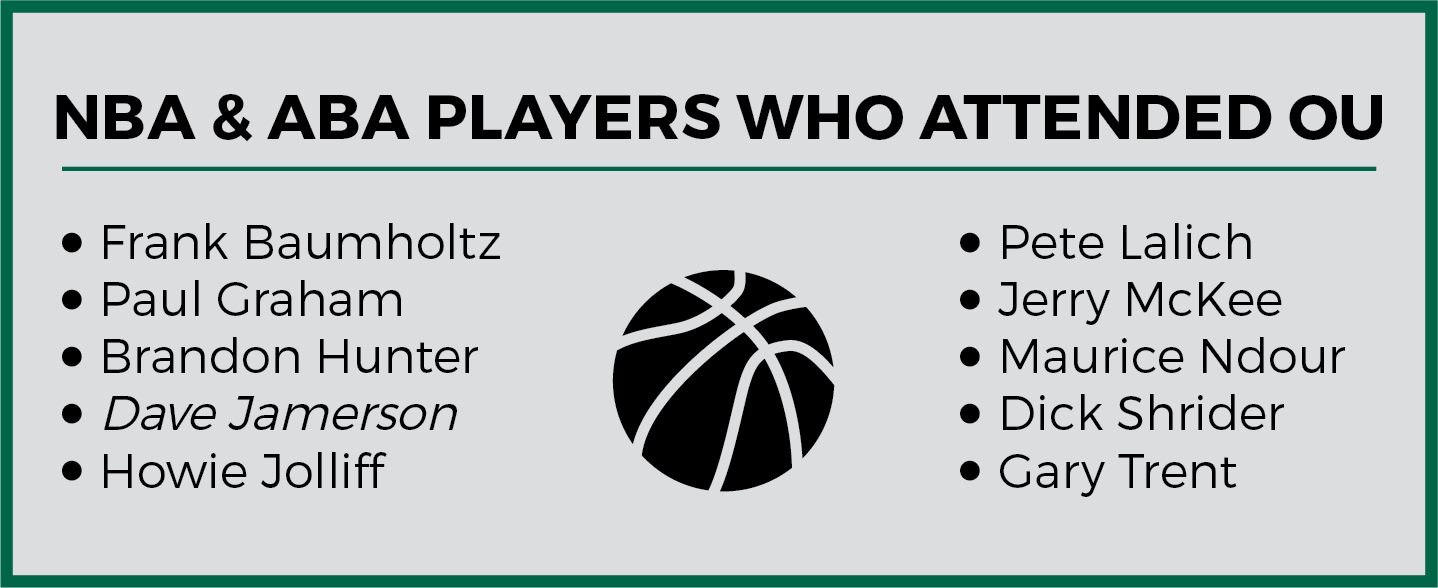

Jamerson is the all-time leading scorer in Ohio basketball history and the only player to score 60 points in school history. He was the 15th pick in the 1990 NBA draft. But most importantly in his mind, he is a servant of God.

Abby Gordon | ILLUSTRATION

It took him a while to get there, though.

Basketball was everything for the first half of his life. It made him famous and it made him a millionaire, which was how he measured his success. But that wasn’t enough.

James Naismith invented basketball with religion in mind.

Naismith was a member of a movement in the late 19th century called “Muscular Christianity,” which combined the teachings of the Bible with intense physical activity.

So Jamerson didn’t find the wrong purpose — it just took him a while to figure out what it was for.

“The game was started for missions,” Jamerson said.

He’s run camps and hosted clinics all over the globe. Over the next year, he has offers to teach basketball and the Gospel to children in Estonia, Nicaragua and Slovakia.

He uses basketball as a tool to spread the Gospel, just as Naismith intended.

When he went to Lithuania, many told him “religion is for the babushka,” meaning the elderly people in Eastern Europe. The young and able-bodied have no use for religion. But when the Lithuanian coaches saw how Jamerson ran his clinic, they respected him enough to listen.

After three hours of shooting drills and schooling the children on the ins and outs of the pick-and-roll, Jamerson gathered the children at halfcourt of one of the three full-sized courts at the Šarūnas Marčiulionis Basketball Academy.

“How many of you have heard of Drazen Petrovic?”

The kids went crazy. Petrovic was a Croatian NBA player who was beloved throughout Europe but died in a car crash in 1993.

“He was amazing. But think about it: Here he was, driving on the Autobahn in Germany. All of a sudden, boom. His car tips over, and he loses his life.“

He concluded his story by citing the words of Marianne Kriel, who spoke at the 2004 Olympics in Athens, Greece. She concluded her speech by saying sport was a great activity, but it couldn’t be anyone’s God.

Jamerson put his own spin on Kriel’s words.

“Basketball is a great sport,” he told the kids. “It’s a terrible God. It ultimately can’t save you.”

It nearly took an act of God for Jamerson to become an NBA player.

In the ninth grade, he was 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighed 130 pounds. Basketball was his third-best sport behind football and baseball.

And yet, he played every weekend because it ran in the family. His father, John, played at Fairmont State, where he played under Joe Retton, the winningest coach in school history.

That winning culture made John an intense competitor, a trait he passed down to his sons, Dave and Tom.

Dave remembers touring the northeast Ohio pickup hoops scene with his dad beginning in 7th grade. He was only allowed to play in certain games, ones his dad knew they would win due to a comfortable matchup.

In one game at Kent State’s Gym Annex, team Jamerson was locked in a 10-10 tie. The next point won the game. Dave got open and received the pass. He remembers shooting an 18-foot shot and missing. The opposing team scored the game-winning basket off his miss.

“You’re the fifth-best player on the floor,” John told Dave. “I don’t care if you’re open. You don’t shoot that shot.”

As Dave got older, he earned more leeway in the Saturday pick up games. He finally hit a growth spurt his junior season, and he became one of the better players on Saturday afternoons.

He remained invisible to college coaches, however.

It took until his senior season to catch the eye of Ohio assistant coach Fran Fraschilla. Fraschilla didn’t go to the 1985 Five-Star Basketball camp in Pennsylvania looking for Jamerson, but Jamerson made himself hard to ignore.

The camp was supposed to take place on the outdoor courts at Robert Morris University. But rain forced the players to migrate inside the gyms of local high schools, which served as an advantage for a sharpshooter like Jamerson.

In one of the scrimmages, Jamerson made six consecutive pull-up jump shots in transition.

“After the fourth or fifth one, there was a buzz in the gym,” Jamerson said.

Jamerson earned a spot in the camp’s all-star game, in which he scored 14 points. But the real show came the morning after the camp ended.

Jamerson’s summer league team from the Akron area was playing a championship game against a team from Cleveland. He was one of five eventual Division I players on his team, including Jerome Lane, who famously broke the backboard on a dunk at Pitt. But he outplayed all of them that morning.

Jamerson poured in 38 points, prompting Fraschilla to call eventual head coach Billy Hahn, who was back in Athens.

“I saw this kid who’s gonna be a pro,” Fraschilla told head coach Billy Hahn. “I don’t think people understand how good this kid’s gonna be.”

Jamerson’s recruiting tour didn’t last long. When he drove past The Convo and Peden Stadium in 1985, he was pretty sure he’d be a Bobcat.

The Bobcats were fresh off an NCAA Tournament appearance and three straight 20-win seasons. Everyone on the team liked each other. He was sold.

“It was an environment that was just so attractive,” Jamerson said.

Jamerson was the sixth man his first season and averaged 14 points per game on a 22-win team. He was thrilled by the idea of averaging double digits on a good team. He considered that alone an accomplishment until one day he walked into College Book Store.

There was a college basketball preview edition of SPORT magazine on the newsstand. As he flipped through it, he realized it was time to start adjusting his expectations.

He was thrilled to be a Division I recruit. He was content bringing his scoring prowess off the bench on a competitive team.

“If I could average 10 points per game on a mid-major power,” Jamerson thought. “That’d be pretty cool.”

He ended up doing a lot more than that. Jamerson said he averaged 30 points a game that summer.

Fraschilla always had a picture of John or Jim Paxson on Jamerson’s seat in the locker room. Fraschilla wrote, “Why not you?” in black marker — a motivation tactic to push Jamerson to aim for the NBA. Jamerson appreciated the gesture, but he didn’t take his potential seriously until he saw his name in SPORT. It ranked him as the fifth-best shooting guard in the nation heading into his sophomore year.

“I was like, ‘Wow, I could really be headed to NBA,” Jamerson said.

In those days, once every four years Ohio toured Europe playing against teams in cities across the continent.

During a game in the Netherlands, Jamerson was in perfect position to tip the ball in the basket. A player on the opposing team sprinted to stop Jamerson from getting the rebound. The player lost his balance and fell straight into the back of Jamerson’s right knee.

Jamerson flew back to OhioHealth Riverside Methodist Hospital in Columbus with Fraschilla, where doctors told him he had torn every ligament in his knee. He was out for the season, and the doctor said he might never regain the same form.

“It was a devastating blow to Jamerson,” Hahn said. “(You’ve got to) understand how much he loved basketball.”

The brace on his knee was uncomfortably large. He still has the 14-inch scar from the surgery. He crutched around campus without a purpose. For the first time in his life, Jamerson began to question the game he loved.

“What am I really putting my trust in?” he said to himself. “Up until that point, all my trust was in sports, basketball and my physical abilities. You get that taken away, and it’s like, ‘Wow, who am I?’”

Jamerson’s first doubt in basketball lasted as long as it took him to get cleared to run. He typically ran a mile in 5:10. His first mile after his rehab took him 7:30.

That was all he needed to kick start his competitive nature again. He went in for two sessions of rehab on some days. If he wasn’t satisfied with his mile time, he’d run another one on the spot.

“I was passionate about basketball,” Jamerson said. “And I was passionate about wanting to get back and play again.”

He got back and played again, all right. During his next three seasons, Jamerson became the highest-scoring player in Bobcat history. His 60-point game against the University of Charleston remains the highest scoring output in school history, as are the 14 3-pointers he made in that game. And he sat out the final 8:33 of that game.

Ironically, the season he missed was the inaugural season for the 3-point line, but he made up for lost time.

“He was always getting up shots,” Hahn said. “Always in the gym. Never went out drinking.”

The Bobcats never won 20 games again during Jamerson’s college career, but he turned himself back into the pro prospect he was before his injury. In his mind, he was ready for the NBA.

He recalled NBA draft night, June 27, 1990, when he was the 15th pick, and the Miami Heat selected him. Shortly after, Jamerson learned he would be traded to the Houston Rockets. There were 50 people at his house watching the draft that night. He’d made it.

Abby Gordon | ILLUSTRATION

Except it didn’t feel like it the next morning. He woke up and made his bed like he always did. He took a shower like he always did. He went out to breakfast with some friends, and nobody out of the ordinary recognized him. Nothing was different.

“I was chasing the proverbial pot of gold at the end of the rainbow,” Jamerson said. “Then you get the pot of gold and you’re like, ‘OK, now what?’”

The NBA was not the validation he’d been seeking.

“He was real cocky to start,” teammate David Wood said. “Had a lot to learn.”

He cracked 10 minutes in a game once before Christmas in 1990, his inaugural season, and averaged just over two points per game over that span. He scored 12 points in a playoff game against the Lakers, but he was probably remembered better for a scuffle with Terry Teagle that got Teagle suspended for Game 2 of that series.

“I didn’t understand how hard I was (going to) need to work,” Jamerson said.

His slow start did not mix well with life on the road. He is very careful about the way he talks about the decisions he’s not proud of. He speaks vaguely, no specifics.

Jamerson recalled Black Friday in 2009 when Jamerson’s wife, April, was glued to the TV. The world was learning that golfer Tiger Woods had cheated on his wife. April was in disbelief, just like much of the rest of the world. The rest of the world, besides Jamerson.

“Watch where this goes,” Jamerson said.

He was right. Over the next few months, countless women surfaced saying they, too, had been involved with Woods. Jamerson knew from the first sign — he had seen it before.

“I’ve been in that world,” Jamerson said. “I know what that world is like.”

Jamerson remembered being on the road when women waited for him in hotel lobbies and by the tunnels after games. Once, Jamerson even had a card sent to his hotel room with a name and another room number on it.

“There was a lot of temptation,” Jamerson said.

There’s a Bible verse he likes to quote that relates to that time in his life.

“Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it.”Matthew 7:13

He shares his testimony all over the world, but as J.K. Jones, a pastor friend of his, said, “You need to be vulnerable enough for people to connect with you, but not vulnerable enough where they’ll lose respect for you.”

The NBA wasn’t what he thought it was. He’d been filling that void with nights out on the town. His life didn’t change the way he’d expected it to, so he began to give in to attention from people he didn't need it from.

In April 1991, Jamerson decided he couldn’t go on alone anymore. He went into his bedroom, dug through his closet and found his black, leather-bound King James Version of the Bible. He probably hadn’t looked at it in five years. But on that night, he needed it.

There was a concordance in the back to help him find the passage he needed. He looked up the phrase, “sexual immorality.”

“The acts of the flesh are obvious: sexual immorality, impurity and debauchery; idolatry and witchcraft; hatred, discord, jealousy, fits of rage, selfish ambition, dissensions, factions and envy; drunkenness, orgies, and the like. I warn you, as I did before, that those who live like this will not inherit the kingdom of God.”Galations 5:19-21

Jamerson can recite a lot of Bible verses, but that one changed his life. It was at that moment, sitting alone in his bedroom and reading about his sins, that he decided he needed to make a life change.

“I’m 23,” he thought. “If I go out and get in a car wreck tonight and I die, I don’t think I’m right with God.”

Jamerson had never heard the word “repentance” before.

When David Wood and Rev. Greg Ball first told him he needed to repent his sins, Jamerson thought they were saying penance, a word he had heard in an Al Pacino movie.

Wood was an instrumental figure in Jamerson’s journey to salvation. He seemed content in a way Jamerson knew he wasn’t.

“I just saw something different in his life,” Jamerson said. “I saw character, I saw the way his marriage was. When he played a bad game, he didn’t tank. He wasn’t up and down.”

At the time, Jamerson lived and died with his performances. Basketball defined him, and his performance on the floor shaped the way he felt about himself.

“Basketball was my God,” Jamerson said. “It was my identity.”

His relationship with his future wife was on the rocks as well. Jamerson and April met during orientation at Ohio University.

They bumped into each other when they were both exploring OU’s campus with a group of friends. They would chat when they saw each other on campus, but that was all until 1988. Over the next few weeks, Jamerson kept running into April outside of his classes, so often he started wondering if other forces were involved.

“I was like, ‘Dude, this is karma,” Jamerson said. “Or ‘The Force is with you,’ whatever.”

It was actually by design. April worked in the Dean of Fine Arts’ office. The women she worked with were big Ohio basketball fans. When they heard April knew Jamerson, they schemed a plan. They pulled up his class schedule and sent April on errands that would put her directly in Jamerson’s path as he got out of class.

Jamerson finally asked her out.

Their relationship got complicated when April moved to Los Angeles to pursue her dance career. They decided to stop dating after their senior year at OU, but Jamerson would visit when the Rockets came to town to play the Lakers or Clippers. They tried to stay in touch, but Jamerson was battling his demons.

They planned a vacation to Hawaii together for the offseason after Jamerson’s rookie year, but nothing was the same. But everything came to a head during a phone call on June 12, 1991. Jamerson was half watching Michael Jordan win his first championship as he talked to April. They sensed their time together was coming to an end.

“You’re not the person I thought you were,” they both said.

Two days later, Jamerson made the official decision to give his life to Christ. He was baptized under Ball’s supervision. The changes were drastic and immediate.

“He stopped talking about himself all the time,” Ball said. “He started caring about other people.”

When Jamerson returned from a lengthy vacation in August, he had a weeks-old voicemail from April and decided to call her back.

They talked about becoming serious about their faith. Jamerson proposed four months later, and they married the next July.

Jamerson’s newfound spirituality helped him on the court, too. He credits how he played more minutes, averaged more points and shot a better percentage than he did the previous season to his faith.

“He played more free,” Wood said. “He had a higher purpose.”

Jamerson and Wood's relationship evolved as they both preached the Gospel to anyone on the Rockets who would listen.

Jamerson even played the sixth man role for the Rockets for a spell until they brought in Eric “Sleepy” Floyd. When Floyd left in the offseason, and the role was Jamerson’s for the taking again.

As he entered his third season, he felt like he was coming into his own as a player.

During a pickup game in August 1992, Jamerson led 2-0. The parallels to Netherlands from his sophomore year of college were eerie.

It was another fast break, this time a four-on-three. Jamerson ran the middle of the floor, trailing the ball handler and former Texas Tech guard Sean Gay.

Jamerson cut to the basket. Gay threw the pass too far behind him. Jamerson tried to reach back, but then pop.

This time, it was his left ACL. He missed the entire season.

The next year, he was the final cut made by the Houston Rockets in the preseason.

“I felt like I came back 95 percent,”Jamerson said. “But 95 percent at that level isn’t good enough. I needed to be at my best to compete at that level.”

He played with the Utah Jazz for the first month of the 1993-94 season. Then he latched onto the Continental Basketball Association’s Omaha Racers and Rochester Renegades. He barely played his final month with the New Jersey Nets.

His career essentially ended when he went home that summer. His brother, Tom, took Jamerson to Kent State to work Jamerson out. But about 30 minutes into shooting drills, he stopped.

“I don’t wanna do this anymore,” Jamerson said.

“Do what?” Tom asked. “Like, this particular drill?”

“Nah, dude,” Jamerson said. “I just don’t have the passion for this anymore.”

They packed up and left.

His career officially ended that preseason after the Timberwolves made him the last cut for the second straight season.

It was time to choose a new path.

Jamerson has a soft spot for athletes when it comes to his work with the church. He shared more than that with Morris Virgil.

Morris Virgil signed a contract with the Chicago Bears, and, like Jamerson, Virgil struggled with sexual immorality and was ready to turn his life around.

Virgil was baptized in Traders Point Christian Church in Indianapolis. Among the those in the crowd was the church’s outreach pastor, Jamerson.

Stories like Virgil’s are what keep Jameron motivated in his religious work.

He spent seven and a half years at Trader’s point as the outreach pastor. He worked with the same passion there that he did on the basketball court.

“He worked just as hard as everyone who needed a paycheck,” said Jim Stanley, Jamerson’s superviser at the church.

Jamerson’s success at the church surprised Stanley. He knew Jamerson had a great had a great work ethic, but in the beginning, he had his doubts about Jamerson’s fit.

Stanley didn’t know if a professional athlete could relate to the everyday person. Jamerson traveled the world and made millions of dollars. A lot of Jamerson’s friends were famous.

“Where’s the common ground,” Stanley wondered.

But he didn’t know Jamerson well enough yet. Jamerson doesn’t keep memorabilia in his house or flaunt his former status.

He laughs when people make a fuss about his NBA playing days.

“That and $4.50 will get me a coffee at Starbucks,” Jamerson said.

His playing days are over. Now he’s focused on spreading the word of God as far as it can go.

Before Traders point, Jamerson planted a church in the suburbs of Indiana with former Colts Mark Thomas. Jeff Saturday, Dallas Clark, Tarik Glenn and other members of the 2007 Super Bowl winning Colts became regular attendees.

In 2015, he planted a new church in Austin, Texas, which has been named one of the country’s 100 fastest growing churches in consecutive years.

The goal is to give people a sense of community, and to take care of the community that surrounds them. The best way to do that, Jamerson thinks, is to spread his faith to and through the people.

“For me, I care about people,” he said. I love connecting people and hearing their stories.”

Landing Page

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.