08.31.16

Domonique Alexander woke up in her apartment from a nap and knew something was wrong. Itchy, pink patches began to form on her skin, and her throat swelled up and started to close.

Just hours before, Alexander had picked up a to-go box at Nelson Court. She had put food in her box only after carefully reading each corresponding food label, complete with ingredients and allergens. Alexander’s nearly fatal tree nut allergy has made her cautious to all foods she does not prepare herself.

She walked over to a tray of coffee cake that, unlike the other desserts, did not have an ingredient card near it.

“I was like, ‘OK, this isn’t labeled — maybe it’s the only one without allergens in it,’ ” the fifth-year senior studying English and film recalled.

When she ate the cake at home, she had an immediate allergic reaction. She took Benadryl, an over-the-counter antihistamine, and fell asleep. Though the medication seemed to work, it wasn’t enough. When she woke up, she reached for her EpiPen to inject epinephrine into her thigh, biding her time until she could get to OhioHealth O’Bleness Memorial Hospital. After her symptoms were cleared with the help of a doctor, she was released to go home later that day

When away from the safety of a home kitchen and reliant on a meal plan, those like Alexander are constantly on guard. Despite that fact, food allergy-related incidents still happen outside of one’s control — facilities and restaurants cannot guarantee the safety of eating foods that may contain, or are processed near, allergens.

Looking back a year later, Alexander said it was her worst allergic reaction to date. Though Ohio University Culinary Services has a policy requiring all meals to have an ingredient card containing allergens and special dietary needs, Alexander blamed herself for the unlabeled cake and not being more careful by asking a chef or a student worker.

15 million people in the U.S. — including one in 13 children — have food allergies.

Angie Bohyer, nutrition educator for Culinary Services, said it’s hard to educate the public on a condition that is without a cure and has so few answers.

A 2015 Food Allergy & Research Education study found 15 million people in the U.S. — including one in 13 children — have food allergies. In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated the number of children with food allergies in the U.S. increased by 50 percent between 1997 and 2011 without understanding as to why.

The Food and Drug Administration identified the eight most common food allergens as milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat and soybeans. Those eight foods account for 90 percent of allergic reactions from food in the U.S. Many other foods derive from those eight, which can limit even more foods for those who are allergic.

The FDA’s Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 states any FDA-approved products must be clearly labeled as containing or being derived from the eight allergens.

Symptoms range in severity, from a simple rash to difficulty breathing as a result of throat-swelling. Each year in the U.S., the FDA estimates anaphylaxis, or a life-threatening allergic reaction to food, results in 30,000 emergency room visits, 2,000 hospitalizations and 150 deaths.

Reactions can be stopped or slowed down by over the counter and prescription allergy medication, epinephrine auto-injectors such as an EpiPen and sometimes prescription steroids and inhalers.

Liz Moughon / For The Post

Chrissy King, a baker at Sweet Arts Bakery and Cafe in Athens, prepares a topping for pastries.

Culinary Services provides weekly menus for all dining halls with icons depicting the ingredients each meal may contain. However, Culinary Services states it “cannot guarantee any item prepared in our kitchen is free of a certain ingredient or allergen” because of times when ingredients are substituted last minute or when commercial manufacturers change procedures out of the dining halls’ control.

Bohyer said in an email that Culinary Services tries to “provide accurate information so that customers can make informed choices,” but she encourages students to ask questions about any risks of cross-contamination.

“One student may put peanut butter on his bread and then unknowingly gets a bit of peanut butter on his finger,” she said in an email. “He then goes to the salad bar and touches the utensils there and contaminates these utensils with peanut butter.”

The university offers appointments to those who want tours and information on food prepared through Culinary Services.

Angela Green, a junior studying social work, took a tour her sophomore year, but she said it’s more important to talk to the chefs

“(The chefs) know what they’re doing,” she said. "Even better than dietitians or any other staff, because the chefs really know what’s in the food.”

Bohyer said all Ohio University food service workers are trained to understand safe food handling practices, but Green said her co-workers throughout her time in the food service industry often don’t follow through even with a sufficient amount of training. For example, they might not understand how important it is to those with celiac disease that food workers change their gloves after handling foods with gluten.

"That needs to be taught more to anyone who’s in the food business, not just the chefs,” Green said.

Green, who is allergic to peanuts and tree nuts, said she once asked about the pizza in a dining hall, and a worker said the dough was made in the same facility as peanuts even though it wasn’t mentioned on the ingredients label on display.

"Peanuts weren’t in it, but they were around it. They didn’t give that warning,” Green said. "People could be taking chances they don’t want to. It just made me nervous and distrust the whole system when you don’t give me that heads up. Maybe someone wants to take that chance, but maybe I don’t.”

Amie Musselman is allergic to 10 different foods, including peanuts. If she even touches or is near peanuts, she could break out in hives.

"People could be taking chances they don’t want to... Maybe someone wants to take that chance, but maybe I don’t." Angela Green, Junior studying social work

Musselman said she lived on East Green and preferred to eat at Shively Court because the food was labeled.

"I really like Boyd (Dining Hall), but while they have the chalkboard (sign) that describes what it is, it doesn’t say what’s in it,” Musselman said.

In 2014, OU opened a gluten-free kitchen in its Central Food Facility that packages and ships gluten-free foods to the dining halls to avoid cross-contamination, Bohyer said.

She added that a station at The District on West Green, formerly known as Boyd Dining Hall, called Margaret’s is free of all “big eight allergens” and is available anytime the dining hall is open.

Though dining halls can be considered safe for those who have food allergies, Green said risk extends outside the walls of Shively and Nelson.

“People bring snacks to class all the time. Sometimes I’m trying to focus in class and someone will take peanut butter out, and I only react if I eat it, but the smell makes me feel so sick, like nauseous,” Green said. “I’ll try to cover my nose with my shirt or something.”

Liz Moughon / For The Post

Jenn Eskey, owner of Sweet Arts Bakery and Cafe in Athens, chooses a pastry for a customer.

A Seattle ABC affiliate reported in 2013 that a woman at the University of Washington had to drop out because the university could not guarantee her safety in classrooms when it came to her allergy.

““I would be really upset about that,” Green said. “That just doesn’t seem reasonable that they couldn’t make some kind of adjustment for her. Somehow, they should be able to do something. It’s kind of ridiculous.”

No allergy-related incidents have ever been brought to the university’s attention, Bohyer said.

Green said she’s not one to make her food allergy everyone’s problem, but because food allergies are so common, she wants students to have the opportunity to express concerns about having snacks in class.

"In class I mentioned I did have an allergy, and it would be nice if no one brought peanuts, and it just makes me feel awkward to ask that,” she said.

In May, Jenn Eskey, owner of Athens Sweet Arts Bakery & Cafe, 817 W. Union St., said one of the more challenging orders she has been requested to bake was an egg-free, dairy-free, soy-free and gluten-free graduation cake.

Eskey already sells gluten-free and egg-free items, but the icing took some trial and error for that cake.

"Gluten isn't in everything, but soy is in everything else so it was interesting to get a cake that was made properly without all of those ingredients,” she said.

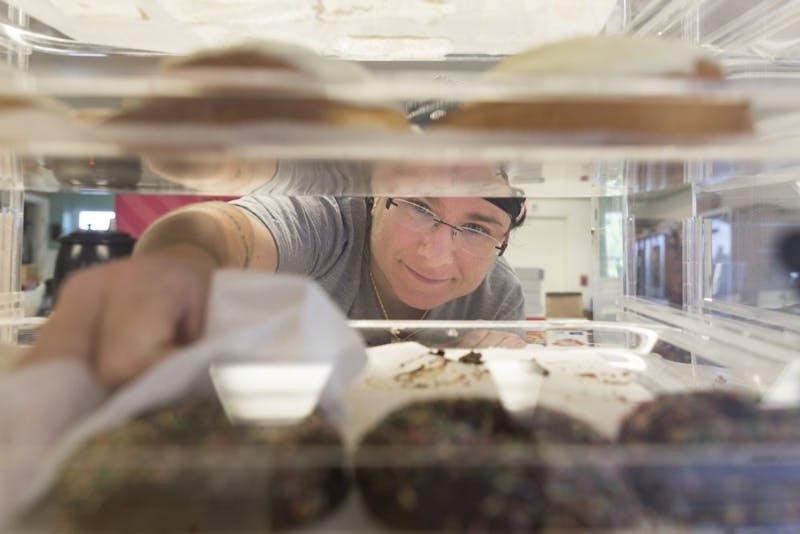

Liz Moughon / For The Post

Chrissy King, a baker at Sweet Arts Bakery and Cafe in Athens, chops walnuts for a pastry topping.

As a business owner, Eskey tries to have a few gluten-free, nut-free options, but large quantities of those baked goods are usually special ordered because the ingredients are harder to come by.

Utensils and bowls used for allergen-free ingredients go through an extra cycle of bleaching, Eskey said. She tries to never cross-contaminate, but those in the food business like her are reluctant to say their methods are foolproof.

Jessica Kopelwitz, owner of Fluff Bakery & Catering, said they have a baker who helps bake gluten-free items as an addition to the menu.

“We train everybody to really know what the ingredients are, what the recipes are just in case people have any questions,” Kopelwitz said. “That’s a big thing for us.”

Kopelwitz also owns West Side Wingery, 9 N. Shafer St., where she made the decision to switch from frying the wings in lard to peanut oil.

“Through advertising, (we’re) making sure people knew that change,” she said. “The last thing we want to do ... is to make everybody sick.”

Since living in Athens, Musselman has been keen on knowing where she can and cannot eat. She has to pass on Chick-fil-A, Five Guys and most Asian foods.

“Texas Roadhouse, I can’t even go near it just because there’s peanuts everywhere,” she said. “Even though I can eat what’s there, I can’t go there because of the surroundings.”

Kopelwitz said like many uptown restaurants, Fluff has warnings posted about allergens and ingredients. But Musselman takes it upon herself to type up a precautionary label about herself.

“I literally have a Word document of all of my allergies. It’s really sad,” she said, laughing.