The institute describes ASL as a language with similar linguistic properties as spoken languages expressed by hand and face movements.

Molly Taylor, a sophomore studying communication sciences and disorders, said people view ASL as English with translated hand signals. There are many incorrect perceptions about ASL. Taylor said that after taking classes, she realized how much she didn't understand ASL culture. In Taylor's first ASL class, her professor taught students the language's history.

"One of the biggest things that struck me was just how much history and recent history there is concerning ASL that we just don't know about or don't hear about as hearing people," Taylor said.

Taylor learned of the injustices committed against the Deaf community in the U.S. during the era after the Civil War. Gallaudet University, the only university where higher education is designed for deaf and hard of hearing students, wrote about this problematic time in a research article. Education reformers during the late 1800s, the university said, asked schools for deaf children in order to remodel their curriculum. Reformers wanted teachers to switch from "manualism," the use of sign language, to "oralism," the use of speech and lipreading. They believed sign language isolated deaf people from society.

"Children in schools, they weren't allowed to sign," Taylor said. "And I had never heard of it. I don't even think sign language was acknowledged as a language with its own grammatical structure in the (1870s) and '80s. And, you know, it is its own language."

Discrimination against the Deaf community isn't just history. In March, the Deaf Services Center, or DSC, fired their deaf executive director and CEO, John Moore, who held the position for over 20 years, according to the Daily Moth, a publication that delivers news in ASL.

Alex Abenchuchan is a deaf host who covers trending stories and deaf topics for the outlet. Abenchuchan said the DSC replaced Moore with Greg Kellison, who has served as director of advancement and community engagement since 2018. Kellison is hearing and doesn't sign.

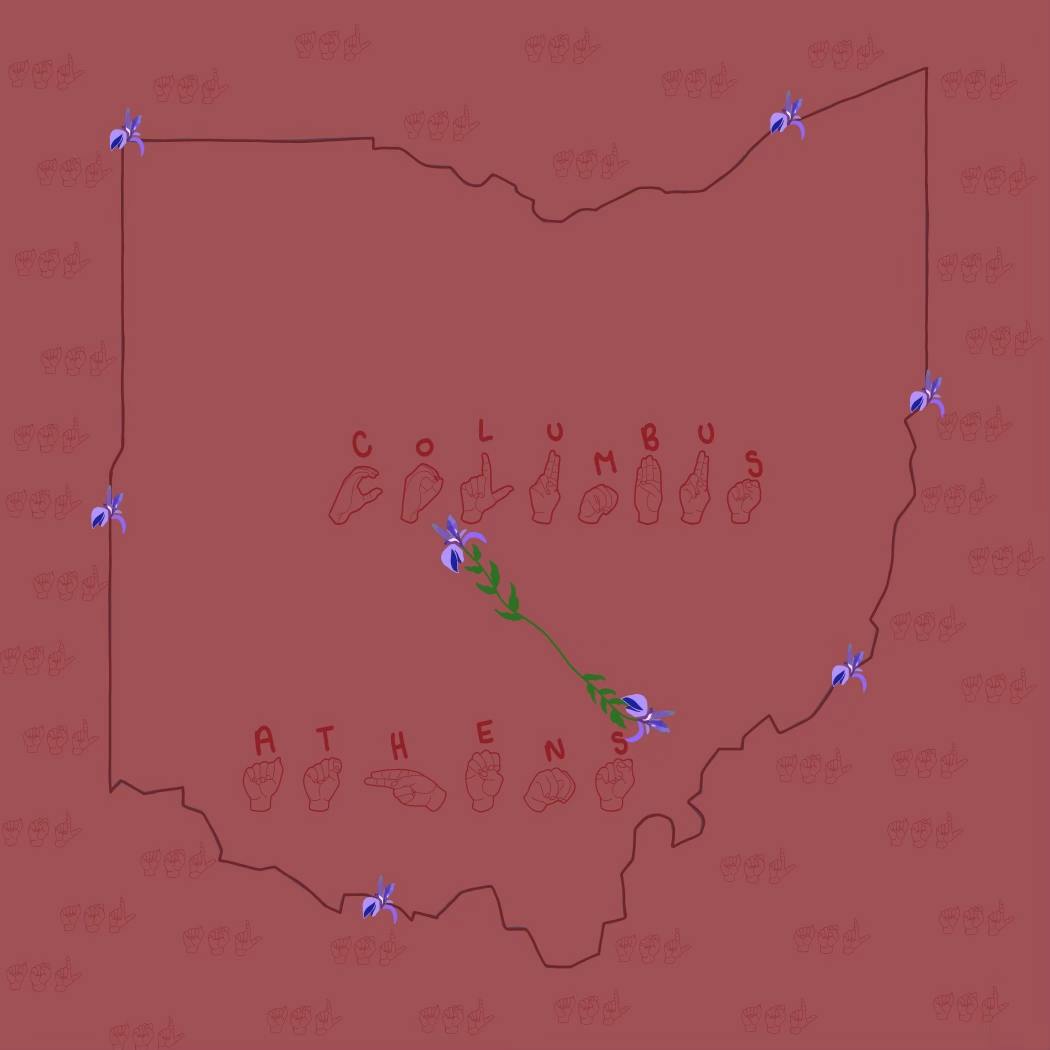

The DSC is a nonprofit that emerged after Ohio established the Community Centers for the Deaf, or CCD, in 1980, according to the organization's website. In 1991, the DSC was created in Columbus to expand services provided by the CCD. Their mission: "To empower the deaf, hard of hearing and deaf-blind and to promote access to communication, services and events in the community."

The DSC announced that Kellison would be the interim executive director in a Facebook post, said Abenchucan. A comment from an account with the profile name Greg Kellison said that Moore was terminated for "failure to exercise fiduciary responsibility." The DSC board also voted unanimously to remove Moore from the position. Deaf Ohioans and others frustrated over the decision protested outside the DSC for weeks after and continue to do so.

McKenna Christy

John Lestina is the owner and president of Heritage Interpreting, a company that connects people with ASL interpreters for events and conversations in Ohio. He said the DSC removed Moore without warning or communication to the Deaf community.

"What they've done is gotten rid of all of the deaf people and put people in place who make decisions who are not part of the community and don't have any idea about the realities of living in the community," Lestina said. "(They're) making decisions without communicating with the community. And it's like a slap in the face."

Lestina is a child of deaf adults, or CODA, and ASL is his native language.

"The Deaf community often considers themselves to be a sociolinguistic minority as opposed to a disability group," Lestina said. "And I've always identified with that as well. I come from that perspective. It's a culture, it's a sociolinguistic minority."

After college, Lestina moved to Washington D.C. to be an ASL interpreter. Lestina then moved to Boston and observed the high standards the interpreting field is held to in these cities.

Interpreters can get a National Interpreter Certification, or NIC, to prove their qualifications. Lestina said that in places such as Washington and Boston, you can't find work as an interpreter without the certification. When Lestina moved to Columbus to be closer to family, he was shocked about the standards held to interpreters in Ohio.

ASL interpreters take on a complex role. The National Deaf Center said: "Interpreting requires a high level of fluency in two or more languages, keen ability to focus on what is being said, broad-based world knowledge and professional, ethical conduct. Interpreters cannot interpret what they do not understand." ASL interpreters are present to serve all parties in a conversation.

"Here in Columbus, most interpreters do not have their NIC and they are not incentivized to go get it," Lestina said. "Why would I spend all this money to earn a certification? And that's the perspective that's very commonly held here. It was a rude awakening. The state of Ohio is one of the very few states left that doesn't have any licensure requirements."

Lestina founded Heritage Interpreting to hold the Ohio interpreting field to higher standards and ethical interpreting requirements.

"I think we're the best and the community has kind of shown that that's what they want," Lestina said. "They want people who are holding themselves to these national standards of interpreting and to be the folks doing it."

People who need an ASL interpreter can contact Heritage Interpreting, preferably a week or more before their event or conversation.

"Whenever anyone needs an interpreter, they can just call, email or go to the website and we're gonna take care of them," Lestina said.

Heritage Interpreting can be called at (800)-921-0457.

Heritage Interpreting got its name, Lestina said, because ASL and interpreting is part of his family heritage and more research is becoming available about heritage language users.

Lestina said heritage language users are people who grew up in homes where one language is predominantly spoken and is different from the one the community around them speaks. For heritage language users, access to interpreters is important. Ohio University works closely with Heritage Interpreting for their own interpreting needs.

Becky Brooks is an interpreter and OU's ASL coordinator. However, since taking on the coordinator role, she doesn't interpret as often. Brooks created the ASL curriculum for OU's Lancaster campus while working toward her Ph.D. in cultural studies with a focus on deafness. Still, Brooks's journey with ASL and interpreting began long before she joined OU's faculty.

"I was born in 1970 and in 1976 Sesame Street hired a deaf actress," Brooks said. "And I just fell in love. I was six years old. I would've been plopped down in front of the television. At that time we had three channels, so there wasn't a lot for my mother to pick from. And I fell in love with sign language, but I didn't really know anything."

Brooks said she had always wanted to be a teacher for deaf children because of her love for ASL. Even as Brooks got older, her passion for ASL didn't fade. But in terms of college, Brooks had an art scholarship to go to the Columbus College of Art and Design.

"And at the last minute, like right before the semester was going to start, I talked to somebody and I found out that Columbus State had an interpreting program," Brooks said.

Brooks got into the program and the rest is history. Along with her passion for ASL, Brooks also believes access to ASL and interpreters is important. She said that ASL can be applied in many circumstances.

"…Access to communication is everything," Brooks said. "And you can't form bonds with your peers if you can't access your peers. Communication is foundational to relationships. And those interpreters provide the bridge to individuals who can't sign or just sign basic."

John McCarthy, the interim dean of the College of Health Sciences and Professions, is working alongside Brooks to create ways for faculty within the college to learn ASL.

"I think in working with our deaf faculty, we have some great faculty who are deaf in CSD," McCarthy said. "And I have always been excited to get to know them. But they're people who, if I have an interpreter and a meeting, I can certainly talk effectively with them. But other times if I see them in the hallway, it's sort of what I can remember from my ASL class, which is getting kind of old these days."

McCarthy said he reached out to Brooks about the idea of finding a way for faculty to learn ASL and Brooks was excited about the opportunity. Brooks, McCarthy said, thought of creating or using an application similar to Duolingo. Another idea is putting ASL lessons on Blackboard for interested faculty to complete at their own pace.

"I knew that language and using language with other people is really important," McCarthy said. "So we said, well, could we also find some ways to get together too?"

There are many blossoming ideas McCarthy and Brooks have to assist faculty in learning ASL. They are starting with a survey to gauge how many people are interested in learning.

McCarthy believes individuals can make language, such as ASL, the most meaningful it can be; they just need to try.

"I think that language is best when we sit down and negotiate our meaning and ideas together," McCarthy said. When you communicate with someone, you do it because you both share a goal to understand something or to share something or to help someone else out or to just participate in a general social ritual. As a college and as faculty and people who are working together, we just have that philosophy."

While McCarthy and Brooks develop ASL lessons for faculty, OU has an ASL club where students interested in learning and practicing the language can come together throughout the school year. Jake Wendling, the former president of the club and OU alumnus, said that the club provides students with learning opportunities and experiences.

"We always do an activity or a game that teaches ASL or practices ASL that they already know,"Wendling said. "We introduce new concepts that they may not see until a higher level ASL course so we try to expose them to that kind of thing earlier. We hold fundraising events and stuff within the community to bring out the deaf and hearing communities together to get that intermingling going on."

Beyond OU, Ohio is home to the fifth school founded for the deaf in the U.S., Lestina said. Lestina is on the board for the Ohio School for the Deaf Foundation and said it's time for ASL and interpreting services to be exceptional here. The Ohio School for the Deaf is a state agency and cannot fundraise, according to Lestina. The Ohio School for the Deaf Foundation fundraises for the school and donates all proceeds.

ASL and the Deaf community have important histories globally and in Ohio. As Taylor continues to learn ASL, Lestina improves the interpreting industry, Brooks and McCarthy make ASL more accessible at OU and they all mutually understand how language shapes our lives, relationships and cultures.

"All of the people we work with on the leadership team either have deaf family members or are deaf themselves or are very close to the Deaf community," Lestina said.

"We all very much share this feeling that not only is it a community we serve, but it's a community that we're a part of, it's a community that we come from, it's our roots." John Lestina, owner and president of Heritage Interpreting