Landing Page

Special Projects

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.

CARL FONTICELLA

02.28.17

This story has been updated to reflect the most recent information.

Had it been up to Quiera Lampkins, one of the best basketball players in Bobcat history would’ve never touched a basketball.

Lampkins is 17 assists away from being ranked in the top five all-time of four categories in the Ohio record books. She ranks second in points, second in steals, sixth in assists and fifth in rebounds.

On March 30, she will participate in the InsiderExposure.com Pro Combine. She has the opportunity to become the first WNBA player Ohio has ever produced.

But when she put on her first pair of basketball shorts at 10 years old, she was ready to end her career before it began. She was self-conscious about how she would look while playing.

“I didn’t wanna sweat,” Lampkins said. “I felt like my knees were ugly.”

Lauren Bacho

Ohio guard Quiera Lampkins (#5) dribbles the ball past Buffalo center Christa Baccas (#44) during the Ohio vs. Buffalo game on Mar. 13, 2015. Ohio beat Buffalo 63-55 during the MAC Tournament. (FILE)

Because of her height, her shorts revealed much more of her legs than her teammates'. She was so embarrassed by her knees showing that she wouldn’t take her pants off before one of her first games to reveal the shorts underneath.

When Andre, her father, threatened to take Quiera home if she didn’t get into uniform, she became more disinterested in playing.

After realizing that wasn’t a realistic option, she begrudgingly took the court. Twelve years later, as the end of her career at Ohio draws near, her name is rapidly ascending through the Ohio record books.

She has played her way onto the short list of greatest players in program history, but what changed?

As her career progressed, the knees Lampkins was so ashamed of became a part of her greatest asset.

When coach Bob Boldon was first hired to coach Lampkins in 2013, one aspect of her game stood out immediately.

Boldon, who had been coaching for 15 years, saw a level of explosiveness he hadn’t seen before, and hasn’t since.

“Her ability to go from stop to start is the best I’ve ever seen,” Boldon said. “That’s the first thing I noticed.”

Taylor Agler was introduced to Lampkins’ athleticism at an early age. Agler began playing against Lampkins in Amateur Athletic Union tournaments when each player was in middle school. Lampkins and Agler grew up 15 minutes apart in Gahanna and Westerville, respectively.

When the teammates would play against each other, Agler knew exactly how to point Lampkins out to her teammates.

“I’d be like, ‘she’s the really fast one,”’ Agler said. “'Don’t let her get by you.’ ”

Occasionally, Agler was tasked with guarding Lampkins. She said she would get frustrated whenever Lampkins would zip by her for a layup.

They were both future Division-I prospects, but Lampkins had an extra gear that Agler couldn’t match. Agler was experiencing the same problem that many in the Mid-American Conference players face today: She just wasn’t quick enough.

Lampkins used her athleticism as her main tool in dominating her early competition. Nobody could stay in front of her or get past her. Agler was thankful when they become AAU teammates in high school.

By the end of Lampkins' high school career, her father’s urging had paid off. She was a two-time All-Ohio Capital Conference First Team member, Gahanna Lincoln High School was 74-26 during her career and she was recruited to Ohio University on scholarship.

But her passion for basketball wasn’t where it is today.

She was good, so she liked that part. But the obsessive work ethic that would propel her to her current heights wasn’t there.

Not yet, at least.

On March 2, 2014, Lampkins played perhaps the most important game of her career. It was also one of her worst.

It was her freshman season with the Bobcats. She entered the matchup with Bowling Green averaging just under 11 points per game.

Her quickness had transferred to the next level. She found that she could still drive to the basket rather easily, even against Division-I talent.

But Bowling Green defended her in a way she had never seen before. They didn’t defend her at all.

She had only attempted 15 3-pointers through 26 games. Knowing how well she attacked the rim, Bowling Green decided to force her to shoot deeper shots.

Lampkins said her defender stood at the MAC logo, about eight feet away from the 3-point line in Anderson Arena, and dared her to shoot.

The result was a five-point performance in 29 minutes. Lampkins made 2-of-8 shots from the field, and went 0-of-3 from 3-point range. She recalls multiple 3-point attempts being airballs.

“She just looked at us like, ‘What am I supposed to do?’ ” assistant coach Marwan Miller said.

Lampkins had no confidence in her jump shot. After the game, she promised the coaches she would never experience a similar situation again.

Oliver Hamlin

Ohio's Quiera Lampkins goes in for a layup during a game against Northern Illinois University on Feb. 6, 2016, in The Convo. Lampkins will be graduating this year and will leave behind a big hole in the Bobcats' roster.

The following summer, she made sure she would keep her promise.

That summer was filled with long sessions in empty gyms with Kiyanna Black and Miller. She worked on her jump shot, but it was the discipline she developed that would help her the most.

Lampkins said her and Black were on three-a-day practice schedule. In the morning, they would go for a run. In the afternoon, they would work on skills.

They would participate in drills such as form shooting, where players shoot with one hand from different places on the court to improve their shooting technique. They would also work with the speed ladder, where they would chop their feet through small holes to improve their quickness.

In the evening, Black and Lampkins would find a gym where they could play pick-up basketball. They repeated the process everyday and pushed each other to improve.

Dating back to their AAU days, Lampkins had always shrugged her shoulders when Black outplayed her in a drill or scored on her in practice. After that summer, she stopped expecting Black to be better than her and starting getting upset about it.

Her unrelenting competitiveness, now so famous around The Convo, was born.

Matt Starkey

Quiera Lampkins (5) drives through contact against Kent State in The Convo on Jan. 14.

The following season, Lampkins shot 32.8 percent from 3-point range, which is still her career-high. Her scoring average has improved in each of her four seasons, and she has developed guard level ball handling skills.

As a result of one of her most embarrassing moments against Bowling Green, she discovered the work ethic that would propel her to become one of the best players in program history.

“I’m glad that it happened,” Lampkins said. “It allowed me to continue to work on my game and grow as a player.”

Lampkins may not have fallen in love with basketball from the beginning, but now she plans on dedicating her life to it.

Her uncertainty about her future isn’t about if she’ll play professionally, it’s about how many professional leagues she’ll play in. The WNBA offseason occurs during the same window as the in-season play for some overseas professional women’s leagues.

“Playing in both wouldn’t be the worst,” Lampkins said. “But playing in one is for sure gonna happen.”

Her coaches and teammates have just as much confidence in her. Agler, whose father coaches the Los Angeles Sparks, said any WNBA team could use Lampkins’ explosiveness.

Boldon believes her versatility is her biggest professional asset. He said she is smart enough to play point guard and run an offense, a good enough defender to be a defensive specialist and cited her career at Ohio as evidence for her scoring ability at the next level.

Miller, who has known Lampkins since she was in seventh grade, bases his faith in her around the fierce competitive nature she has developed at Ohio.

“She ain’t afraid of nobody,” Miller said. “She don’t care who you are, you can get this work just like anybody else.”

Before she gets a chance to show her talents to pro scouts at the combine, Lampkins has work to do.

She has made progress with her jump shot, but she knows it can still improve. Her driving ability is unmatched by any player in the MAC, but she still believes she can be a more consistent finisher.

After the season is over, Lampkins will still be in the gym every day. More shooting drills, more running, more speed ladder work.

But for someone who never wanted to play in the first place, she seems to be ok with working on basketball for a few more weeks.

“I’m definitely glad (my dad) made me play,” Lampkins said. I’ve put a lot of work in, and to see myself grow as a player, I have respect for myself.”

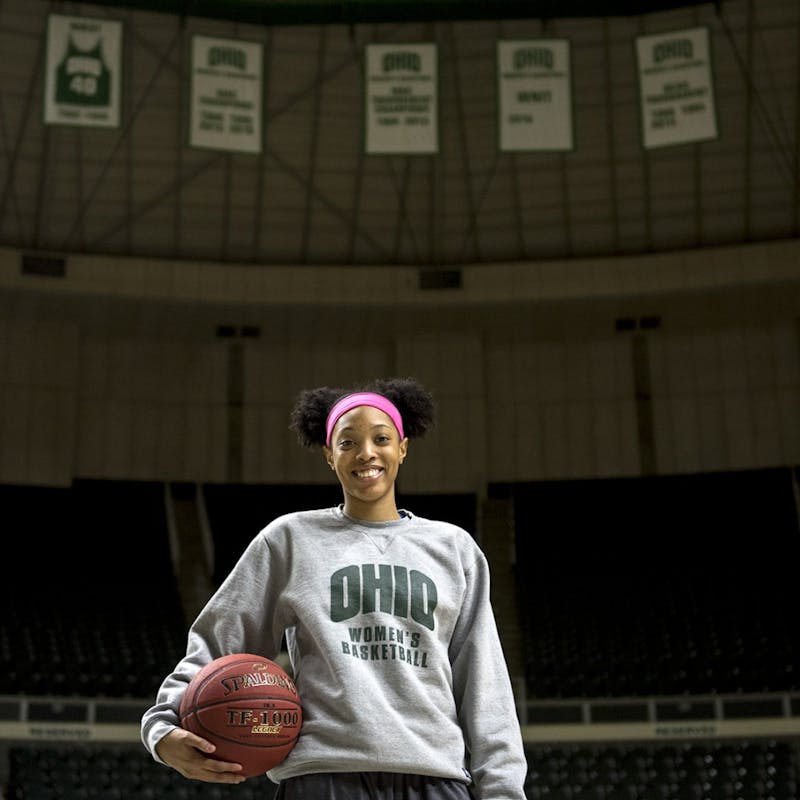

Carl Fonticella

When Ohio senior guard Quiera Lampkins graduates, she'll be considered one of the best in Ohio's history, but she never would have become a basketball player unless her dad, Andre Lampkins, forced her to begin to play at the age of 10.

Landing Page

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.