Landing Page

Special Projects

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.

CARL FONTICELLA

02.07.18

Amongst the trees, the hills and the hollows in Appalachian Ohio lies a sight that, to the outside viewer, may seem otherworldly. It isn’t the sight of a collapsed mine or massive coal piles, but rather another blemish. Acid mine drainage — water rich in iron oxides and other trace metals — contaminates local waterways and turns them either deep orange-red or silvery-blue hues.

Polluted water flows out of old coal mines and into creeks, creating a stark contrast against the rich green tones of the trees and the forests. As a result, the streams take on an alien-like appearance.

“It was commonplace to see orange and red water flowing out of mines,” Michelle Shively said. “And because of that, for generations, no one paid much attention to it.”

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Hewett Fork, located in Carbondale, is heavily polluted by acid mine drainage and there is a doser located near where the polluted water flows into the creek.

Shively, the watershed coordinator for the Sunday Creek Watershed Group, first started doing field research for the Voinovich School as an undergraduate student at Ohio University.

Although most of the mining operations in southeast Ohio have gone away, the consequences that it created are here to stay. According to scientists and researchers at the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, acid mine drainage can be produced from mines for hundreds of years after closing down. That is because of the cyclic water cycle and constant refreshing of the groundwater and water that flows into the underground mines.

Those scars left behind by mining are not easily fixable, from the coal deposits, to the stripped land in the Wayne National Forest, to the larger problem of acid mine drainage. There are dedicated conservationists, however, working in the southeast Ohio area for the last 20 to 25 years trying to reverse the damages done by prior generations.

A pH of about 6.5 to 8.0 is ideal for healthy streams, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA. The tainted water that flows out of the old mines has an alarmingly low pH value, with some sites at Sunday and Monday creeks in Athens County having tested at pH values of 2 to 3 as recently as 2009. That’s the same pH level as pure lemon juice.

“It was commonplace to see orange and red water flowing out of mines. And because of that, for generations, no one paid much attention to it."- Michelle Shively, the watershed coordinator for the Sunday Creek Watershed Group

Even though mining government regulations came into play in the late 1970s and early 1980s, acid mine drainage has continued to be a problem and will continue to be so for decades to come, Shively said.

The mineral pyrite, commonly known as “fools’ gold” because of its color, is found in the ground in southeast Ohio, and when exposed to oxygen, it forms sulfuric acid. The reaction to oxygen and subsequent chemical reactions over time lead to the breakdown of pyrite, which pollutes the water. The reddish-orange color that is seen in Sunday Creek, Monday Creek and Hewett Fork near Carbondale is due to ferrous hydroxide, while the silvery-blue color of Snow Fork — Monday Creek's most polluted tributary — is the result of aluminum as the trace metal.

Dating back to the 1800s, mining has driven the economy and has helped create towns in Appalachia. But, with every positive comes a negative. Throughout the 1900s, much of the mining that was done in southeast Ohio was unregulated, and caused disregard to the environment and the surrounding areas. In a 2001 study done by the Voinovich School, 341 miles of streams in Ohio were affected in some way by acid mine drainage. Researchers also tested 175 miles of streams in 2010. Of that, only 23 percent of streams were considered healthy enough for plants and animals.

For so long, the message and sentiment surrounding acid mine drainage was one of hopelessness and despair. Gone are the conversations about how polluted the region is, and they have been replaced with hope that species will return to the streams and life can flourish once again.

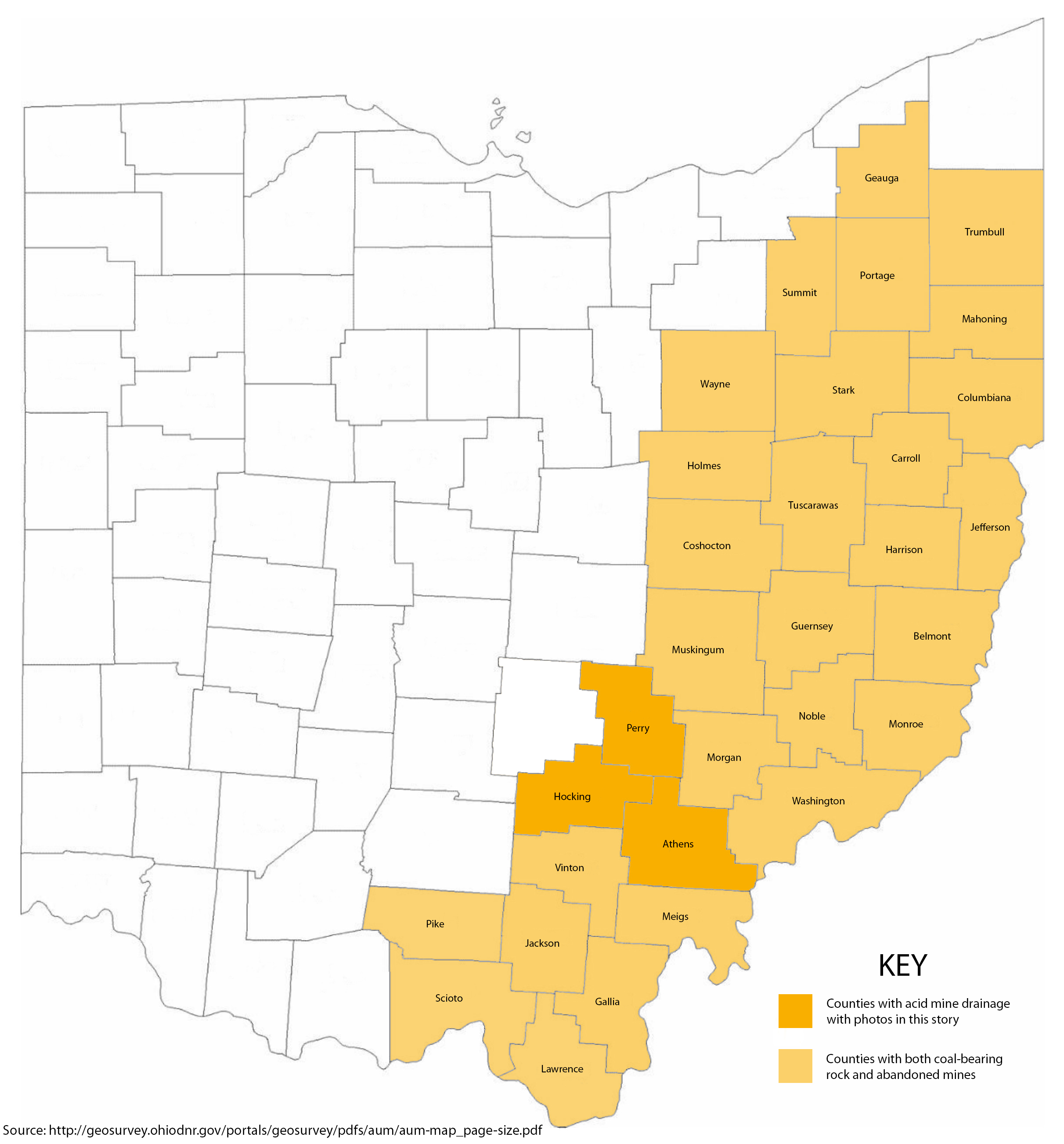

Coal mining began in Ohio in the early 1800s, with most of the mines existing in the eastern and southern parts of the state. About two-thirds of the coal that was mined in Appalachia is a result of underground mining; the rest is by surface mining, according to a 2005 report from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, or ODNR.

By 1898, there were almost 1,200 underground mines operating in the state, but Nate Schlater, watershed coordinator at Monday Creek Restoration Project, said the true number of mines would never truly be known because a lot of families mined for themselves on their own properties and never reported to the government that mining took place on their land.

Most mines have either been torn down for years or now lie on private property, but the ODNR pinpoints mines in each county. Results of strip mining are also on full display in the Wayne National Forest, with small coal deposits on the ground and visible scars on the hills.

According to the U.S. Forest Service within the Department of Agriculture, it’s estimated there are about 4,600 identifiable underground coal mines in the state of Ohio via maps, with another 2,000 to 4,000 mines existing, but they were never mapped. Since 1800, 2 billion tons of coal has been mined on about 600,000 acres of coal-bearing land in Ohio.

Because a majority of the mining that was done in southeast Ohio was underground mining, it created an environment that was perfect for the creation and sustained presence of acid mine drainage. Coal production hit its peak in 1970, when more than 55 million tons of coal were mined. When the mines began to close in the years following, water was poured into the empty mine cavities. Because of the pyrite that is found in the ground along with coal, the chemical reactions between water, oxygen and pyrite formed acid mine drainage.

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

The Majestic Mine opening is just a short drive east from Movies 10 in Nelsonville, right off of U.S. Route 33. The ground surrounding the mine opening is so polluted that even when the area hasn't seen much rain, the mud is a bright orange and is that color inches deep into the ground.

“If you have an underground mine, once we’ve gone in and pulled that coal out, then you’re left with these big rooms and pillars. … So there’s big void spaces that are the rooms where they took the coal out, and the pillars that are left hold up the roof of the mine and the surface of the ground,” Shively said.

Shively said there are three main components that create acid mine drainage. Water, oxygen and pyrite are exposed on the walls of a room. Chemical reactions start to occur and sulfuric acid is created.

“These mines can pump out acid mine drainage for hundreds of years. It’s not a problem we can solve overnight and most of the work that we’re doing is treatment, it’s not preventing," Shively said. “Unfortunately, there’s not an easy fix; otherwise, we would have done that already.”

Another reason as to why acid mine drainage has the potential to flow out of mines for the foreseeable future is because of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977. Shively said a lot of the mining had long since finished in the area. Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act created two programs: regulating active coal mines and reclaiming abandoned mine land.

Upon first glance, the life in the streams and creeks in southeast Ohio appears nonexistent. Both Sunday and Monday creeks are about 27 miles long, but the creeks are not fully polluted or have an unbalanced pH level. There are two discharge sites along Sunday Creek that spew out acid mine drainage in both Corning and Truetown. Monday Creek is threatened by the aluminum-heavy Snow Fork, a tributary that flows through Murray City. Trace metals in the water dictate what color the pollution is: Iron gives the water the unmistakable orange and red hues, aluminum stains the water a silvery-blue and manganese — another trace metal found in this area — can turn the water black.

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Snow Fork, a tributary of Monday Creek that flows through Murray City, offers a different view of acid mine drainage. Because the trace metal found in the water is aluminum, it is colored a silvery-blue instead of the bright orange.

In the early 1990s, the Ohio EPA declared both Sunday and Monday creeks uninhabitable, and the consequences of decades of unregulated mining wreaked havoc on the habitats.

Many groups operate — and many more partner with Rural Action, formed in 1992 — to provide continuous care to the waterways of southeast Ohio. Two of the largest groups, Sunday Creek Watershed Group and Monday Creek Restoration Project, operate out of Trimble and New Straitsville, respectively. Monday Creek Restoration Project was formed in 1994, and Sunday Creek Watershed Group was formed in 1999.

Two main cleanup efforts are creating limestone-resting pools for water and water quality testing/electrofishing to gauge the health of the creeks. Limestone is introduced to the polluted water because it helps to balance out the pH levels. Schlater said limestone is a naturally basic material, which can help level out the acidity of acid mine drainage. The group has a couple of limestone pools around the Athens area, however one of the largest one is to the left off of Happy Hollow Road on the way into Buchtel just after getting off U.S. Route 33.

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

These are limestone resting pools located just off of Happy Hollow Road in Buchtel. If you get off of U.S. Route 33, this will be off to the left as you drive into Buchtel.

Electrofishing, as the name implies, uses electricity to catch fish. The electricity is used to bring fish out of hiding spots in the creek. The charge of the lead net is only around 2 amperes and doesn’t fluctuate based on what kind of fish they hope to catch and record. The process involves multiple team members: one on lead net, two on assist nets and one who makes sure that the extension cord that leads from a generator doesn’t get caught on any branches or rocks in the creek.

From a center point that is designated by the generator, they will go a quarter-mile upstream and downstream, gathering any kind of life form so they can get an accurate description about what is living in the creeks. They go out about once every couple months so they can see the amount of change, if any. A first impression of the creek might give the impression that hardly anything lives in the stream, but that certainly isn’t true. At a site in Jacksonville, over 19 species of fish and about 260 individual fish were recorded in a half-mile stretch of Sunday Creek.

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Electrofishing is usually done by multiple team members, with one on lead net, one or more on assist net, and then another person ensures that the extension cord from the generator doesn’t get stuck on any rocks or branches. This is at a site north of Glouster off of State Route 13.

Due to the cleanup and reclamation efforts that both teams have done, species of fish and bugs have returned that haven’t been there in generations, Schlater said.

“I remember an older gentleman came in with his grandson a few weeks back, and he said that they just got done fishing and saw a Longear Sunfish, a fish that hasn’t been in Monday Creek for generations,” Schlater said. “He was proud to have shared that moment with his grandson.”

At the Monday Creek office in New Straitsville, there is a fish tank with species of fish that are found in Monday Creek. Schlater and the other team members knew if they were to have a fish tank when Rural Action was founded, they would have been lucky to have gotten just one fish.

A majority of members are either locals to the greater Athens area or have lived in Appalachia for most of their lives. When the conservation work started, Monday and Sunday creeks were, for all intents and purposes, dead. Most of what was talked about back then was the doom and gloom of what acid mine drainage was, how it was caused and the damage it had on the watersheds. Today, however, their message is one of hope, one of optimism. The work they’ve done has ensured that species are returning to streams, and the water is slowly and surely becoming healthier.

But, Shively said, there is still work to be done. Polluted water will be pouring out of mine openings for hundreds of years to come, and, because water, will always make its way to the ground, it is foreseeably the hardest barrier they will have to hurdle.

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

Both Murray City and New Straitsville, like many of the towns in southeast Ohio, have been on the front lines of the coal industry. According to Monday Creek’s website, the EPA identified acid mine drainage to be the No. 1 problem affecting water quality in Appalachian Ohio. The Office of Surface Mining has suggested that southeast Ohio has “some of the most seriously acid mine drainage-impacted streams in the United States.” As for Sunday Creek, the office estimated that 38 percent of the area in the watershed has been deep mined for coal, meaning that instead of surface mining. In an effort to try and reduce the impact, Rural Action has implemented a multitude of large projects in the area.

According to data on their websites, Sunday Creek Watershed Group has completed six major projects totaling nearly $1.2 million and a seventh project in progress. Monday Creek Restoration Project has completed 12 projects totaling $3.4 million. One of those projects that Monday Creek helped to create was the Essex Doser site, which was closed in 2008, but created a new doser at Monkey Hollow near Carbon Hill in 2014. Schlater said the high acidity of the water from the mine at the Essex site caused rapid decay to the equipment, which made the constant repairs not cost effective.

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

The Monkey Hollow Doser Project, located in Carbon Hill (a census-designated place in central Ward Township, Hocking County) was built in 2014 after the initial doser site was moved here.

“Some of the work that we are doing (at OU) is assessing places that have been reclaimed and whether or not the reclamation works, and that’s important because you spent money, and you want to see if there is recovery,” Morgan Vis-Chiasson, department chair of the environmental and plant biology department, said. “Some of the goals of recovery are having good water chemistry and if you have that, you can also see that the biology starts to come back as well. But there are some places that I think would be far too costly to actually reclaim from the legacy of acid mine drainage.”

Throughout the last couple years, those affiliated with those conservation groups are witnessing results from their hard work and because of that, they can start to focus on other environmental issues in southeast Ohio. Shively said at Sunday Creek they want to start projects focused on riparian restoration, and working to save endangered species.

“For the longest time we’ve only been focused on acid mine drainage in our area because it’s been the most detrimental so we could have done all the wastewater and septic work, but we still would have had dead streams because of acid mine drainage. But because we’ve been working on that, other projects are now able to open up,” Shively said.

The loss of jobs and the dwindling of towns and the economy came along with the decline of mining in the southeast Ohio area from the 1970s onward. Mining towns like Jobs, San Toy, Moonville, Vinton Furnace State Forest, Kings Station and many others that were once booming communities with thousands of people have now been reduced to either ghost towns or places with just a few houses.

According to the ODNR, the annual coal production for the state of Ohio declined 59 percent between 1970 and 2003. Per a 2018 report by the Appalachian Regional Commission, coal mining jobs fell 27 percent between 2005 and 2015.

Coshocton-based Oxford Mining Company proposed plans to mine in a 300-acre area for five years in the Trimble State Wildlife Area in Athens County. Plans have been in the works since 2014, but the Athens County Regional Planning Commission approved activity to surface mine the area in 2016. Of the 300 acres, 57.2 of them would be impacted by surface mining, and the company plans to extract about 1.16 million tons of coal valued between $46 million to $52 million.

Local residents, whether environmental activists or just concerned citizens, voiced their concerns at local public meetings put on by the ODNR. Per an application submitted to the Ohio EPA by the Oxford Mining Company, the land it plans to mine on is near the Sunday Creek watershed, an ecosystem that remains fragile even after the amount of time and effort that Rural Action has put in to reclaim land from the stain of acid mine drainage.

“Not only are we doing the scientific work and the research and the restoration, which is all important work, but we’re also part of the community,” Shively said. “We’re investing in people and the place and the environment … I’m proud of the work that we do and I’m glad I get the opportunity to be a part of it.”

Carl Fonticella | PHOTO EDITOR

A Brindled Madtom catfish fry rests in the hand of Amy Mackey, Coordinator of the Raccoon Creek Watershed Program, after being caught at an electrofishing site near the Athens County Dog Shelter in Chauncy.

Landing Page

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.