Landing Page

Special Projects

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.

ABIGAIL DAY

02.22.18

A sea of umbrellas made its way across campus as students rushed to escape the gloomy day the Athens weather granted them. The rain fell in sheets. The wind cracked against the windows of Lindley Hall’s castle-like expanse on a dreary Feb. 14 afternoon. The noise from the sidewalks became quiet as students and professors retreated into coffee shops and classrooms.

Inside a cramped lecture hall on the third floor of Lindley, damp umbrellas at their sides, about 20 Ohio University faculty members gathered to discuss their concerns about the university’s financial past, present and future.

They spoke with apprehension in their voices, riddled with concern about potential layoffs and raises, wondering if the university’s fluctuating enrollment will affect their jobs. All of their concerns built up to what they called the ongoing university “budget crisis.”

The university budgeted for $53.2 million in operating results for fiscal year 2018 — a decline of nearly 50 percent from the prior year.

Ask the OU administration what defines a budget crisis, and they’ll say it’s not really a crisis at all. Ask the faculty members sitting in Lindley, and the mood is somber.

Loren Lybarger, president of the OU chapter of the American Association of University Professors, stood in the front of the room and listed off the items of chief concern.

Repercussions from the tightening budget are seen as urgent matters from faculty. The effects are being seen much sooner.

“Firings. Shrinking of the faculty through attrition and non-replacement. Loss of academic programs, potentially. And a whole host of other possibilities,” Lybarger said. “And this is the message that we’re getting from Wilson Hall.”

Cutler Hall, the crown jewel of OU’s campus, is perched just next door to Wilson, which houses the College of Arts and Sciences — a college hit especially hard by budget constraints. Despite the proximity of the two buildings, Lybarger said, OU President Duane Nellis is painting a “very different picture” from his Cutler office.

“He sounds much more optimistic,” Lybarger said. “He’s talking about investing and honors programs and giving the faculty a raise. So it’s not at all clear where things lie exactly.”

Inside Cutler, the mood is starkly different. The urgency that exists among faculty members is diluted. The vice presidents speak of optimism and plans for growth academic programming.

Vice President for Finance and Administration Deborah Shaffer stressed that, on many metrics, the university is stronger than ever. Though demographics have been changing, she said, enrollment is at an “all-time strength level.” Market shares have been increasing. Despite “failing” facilities, the university is investing in capital projects.

“I wouldn’t call it a crisis,” Shaffer said. “The analogy I would use is similar to the market — we’re going through a correction period. That’s the best analogy to think about what’s happening to the university.”

But whether it’s termed a crisis or a correction period, fear of cuts to faculty and academic programming have tensions running high on campus and have prompted a host of questions. The rift between the administration and faculty members is one for how the “crisis” should be handled.

A university budget is a living, breathing document. It’s thousands of pages of spreadsheets and numbers that change constantly, pored over by top administrators, scrutinized by board members and ultimately, impacting every facet of what happens on campus.

There’s no simple way to break down the many factors that play into its flux and flow.

Interim Executive Vice President and Provost Elizabeth Sayrs knows people want answers to the uncertain future quickly. But the “better answer,” she said, takes time and conversation.

“I think one thing that’s hard for anyone to understand ... is that when you think about your budget at home, you know how much you’re going to bring in every month. You know how much the rent is. It’s very clear,” Sayrs said. “The university budget is not like that at all.”

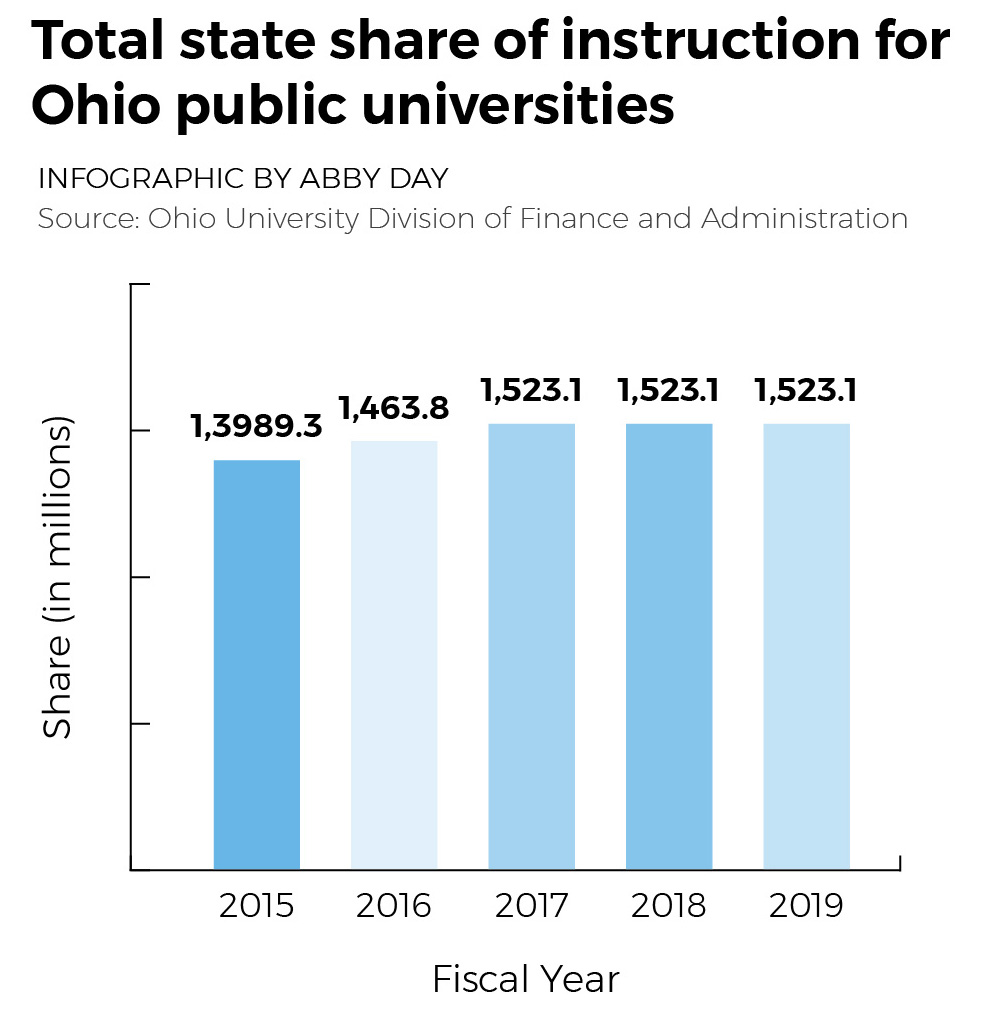

Public universities in Ohio are receiving less funding — or “state share of instruction” — from the state. Throughout the past 15 years, the level of state support for public universities decreased from 35 percent of OU’s total budget to 20 percent. On top of that, Ohio Gov. John Kasich’s 2017 state budget included a freeze on tuition increases for public universities.

“This is a higher education dynamic,” College of Arts and Sciences Dean Robert Frank said. “The way Ohio does its budget makes it very hard to plan, because you’re held hostage until June of every other year.”

The university, however, is still able to increase tuition for the class of 2021, because the freeze would not impact students on guaranteed tuition.

In January, the OU Board of Trustees voted to increase tuition for the next cohort of students by 1.3 percent, or about $155 per year. The board also approved a 3.5 percent increase in residential housing rates on the Athens campus, as well as a 2 percent increase in rates of campus culinary services, according to a previous Post report.

As the state draws back on financing higher education, schools like OU face widening gaps in revenue and expenses. Factor in elements such as inflating health care costs and deferred maintenance — the backlog of major maintenance projects — and problems arise.

“You can see how costs are going to increase when revenue isn’t increasing,” McLaughlin said.

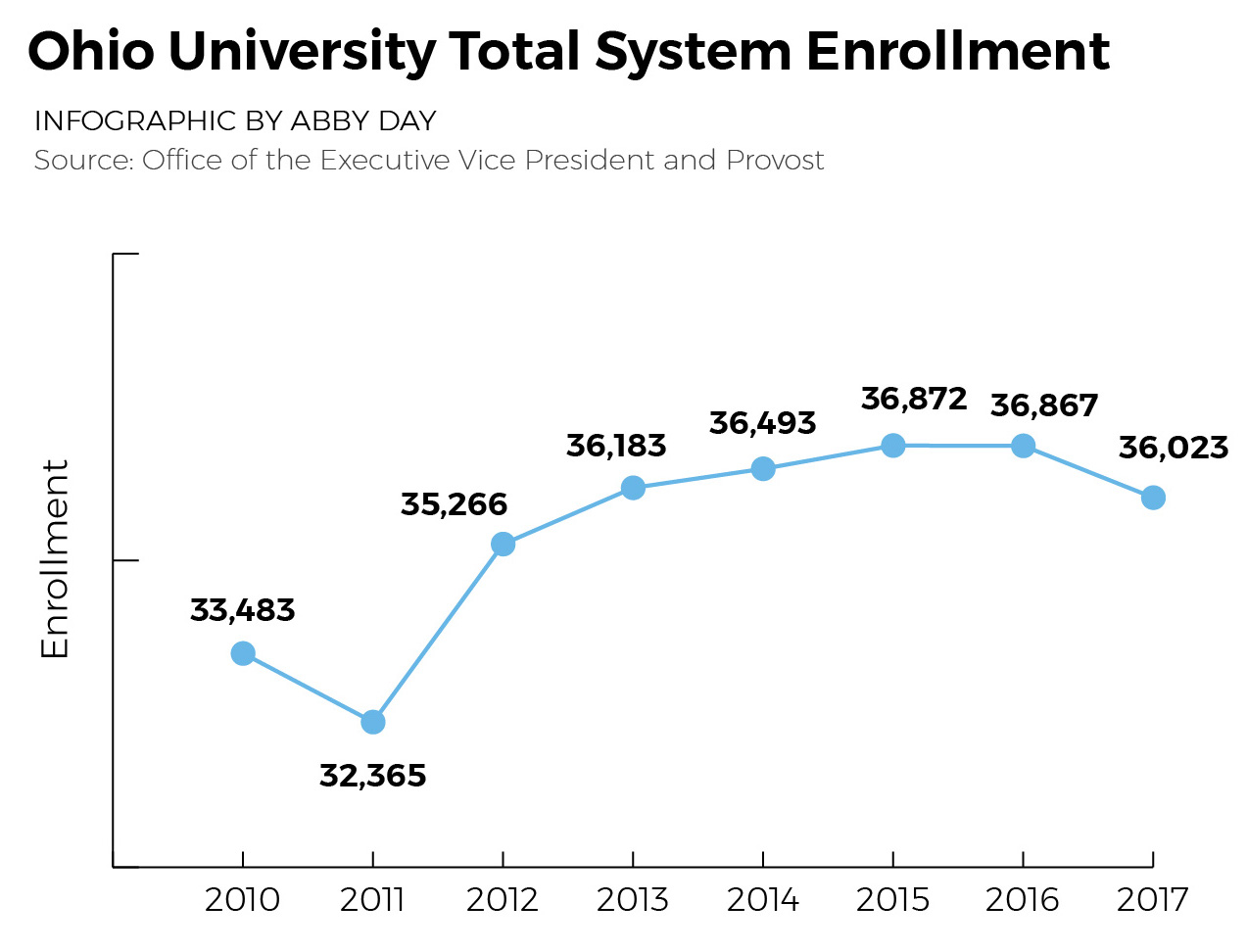

Another problem stems from what Shaffer calls “changing demographics” in enrollment.

The most recent freshman class enrollment of 4,045 students was 264 fewer than the previous Fall Semester enrollment numbers. Meanwhile, the university saw 87 fewer transfer students than it was originally budgeted for.

“Not a lot, but it’s enough when we were projecting a little bit of growth,” Nellis said. “You know, a couple hundred students from in-state — that’s $2 or $3 million just like that from tution, let alone the other revenue for residence halls.”

If there’s one observation that seems to ring true to both faculty and administrators alike, it’s that a lack of communication has soured the budget planning process and led to widespread confusion — or “gloom and doom,” as Lybarger put it.

“One of the problems I think that we’ve encountered collectively is the lack of information,” Lybarger said. “The lack of transparency about the severity of the crisis and about what the administration is understanding to be the response that it will take.”

Meanwhile, McLaughlin said a significant part of the confusion stems from miscommunication both among the administration and between the administrators and faculty.

That sentiment is one that echoes in Cutler Hall.

“I do think we could have done better collectively,” Shaffer said. “And when I say ‘we,’ I’m not necessarily saying Cutler Hall, but we as an institution need to do better communicating.”

In December, Nellis, not yet a year into the presidency, said budget issues have been “one of the big challenges” he has faced in office. He wants the university to be able to give raises to faculty, staff and graduate assistants whose pay has been stagnant.

“And that’s a challenge, given the budget situation,” he said. “But it’s really important.”

The likelihood of the layoffs that Lybarger spoke of remains largely uncertain, according to the administration.

In April 2017, the Finance and Administration department eliminated 12 positions, leaving five university staff members without jobs. The layoffs were coupled with $4.9 million in cost reductions submitted by administrative offices, in addition to $4 million in anticipated reductions in the next two fiscal years, according to a previous Post report.

The budget gaps that need to be rectified could ultimately lead to changes in personnel, Nellis said, although it’s “still too early” to determine the scope of potential layoffs.

“If you want sort of a guarantee that that’ll never happen, that’s not something that can be offered,” Frank said. “But I can tell you that, as far as I can tell, people are working very hard to minimize or avoid that.”

In an effort to prepare for potential budget cuts, Sayrs said academic colleges were asked to consider how a 7 percent blanket reduction to their budgets for the next fiscal year would impact their operations. All academic support and administrative units are already reducing their budgets by 7 percent in the next three years.

“We’re really working hard to understand in infinite detail what the scale of the problem is,” Frank said. “Which may seem like it’s an easy thing to figure out. But you’re projecting into the future, in order to make decisions now. Telling the future is a real challenge.”

Frank said the size of the reductions is “up in the air right now” — colleges, however, have already begun looking closely at cuts.

“We all know we don’t have a final budget,” McLaughlin said. “But we’ve already had to make decisions within our units.”

Whether state funding will improve, Shaffer and the budget planning team make no certain plans. The share of the state budget, she said, is the university’s “new reality.”

“I wish I had a crystal ball,” Shaffer said. “We are not planning for it to get worse, but we’re not planning for it in any way to bail us out or change.”

With the shuffling of positions and ongoing searches within the higher level of university administration, some faculty members question the likelihood of change. McLaughlin, however, has faith in OU leadership.

“I spend a lot of time with these people. So maybe I’ve drank the Kool-Aid,” McLaughlin said. “But I have some optimism there in the sense that I have faith right now that we have a president and (provost) who are probably going to do the best we could expect in the climate.”

Shaffer thinks some of the “angst” coming from faculty goes back to a desire for facts.

“I think people are hungry for information,” Shaffer said. “And we’ve been working to get that information and education out and as people get that, they're more able to focus.”

But the information is largely inconclusive, for now.

Lybarger fears that if faculty shrinks, the shrinking of academic programs will follow, and the university’s standing will be negatively impacted.

While messages from Cutler Hall exude hope, Lybarger said the dean of his college is sending out “nothing but doom and gloom.”

And that doom and gloom — the uncertainty surrounding layoffs, raises and enrollment — has faculty members wondering what the future truly holds.

Landing Page

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.