Landing Page

Special Projects

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.

SARAH OLIVIERI

04.16.16

As the sun set on a cold February afternoon, 100 people gathered on and near Templeton-Blackburn Alumni Memorial Auditorium’s portico to speak out against rumors of a “resurgence” of the Ku Klux Klan in southeast Ohio.

Several speakers shared their stories to celebrate diversity in Athens and the surrounding region, one historically thought of as almost exclusively white. With an introspective rally as the backdrop, attendees wanted to prove an important point: Black lives matter, even in Appalachia.

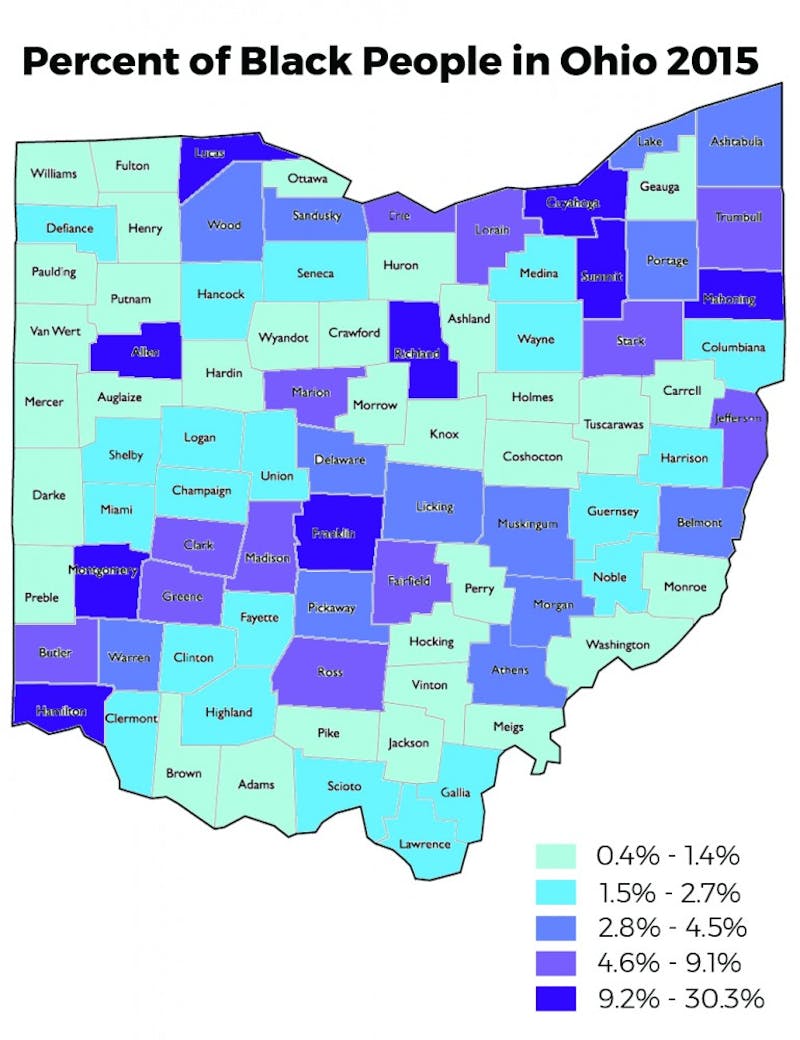

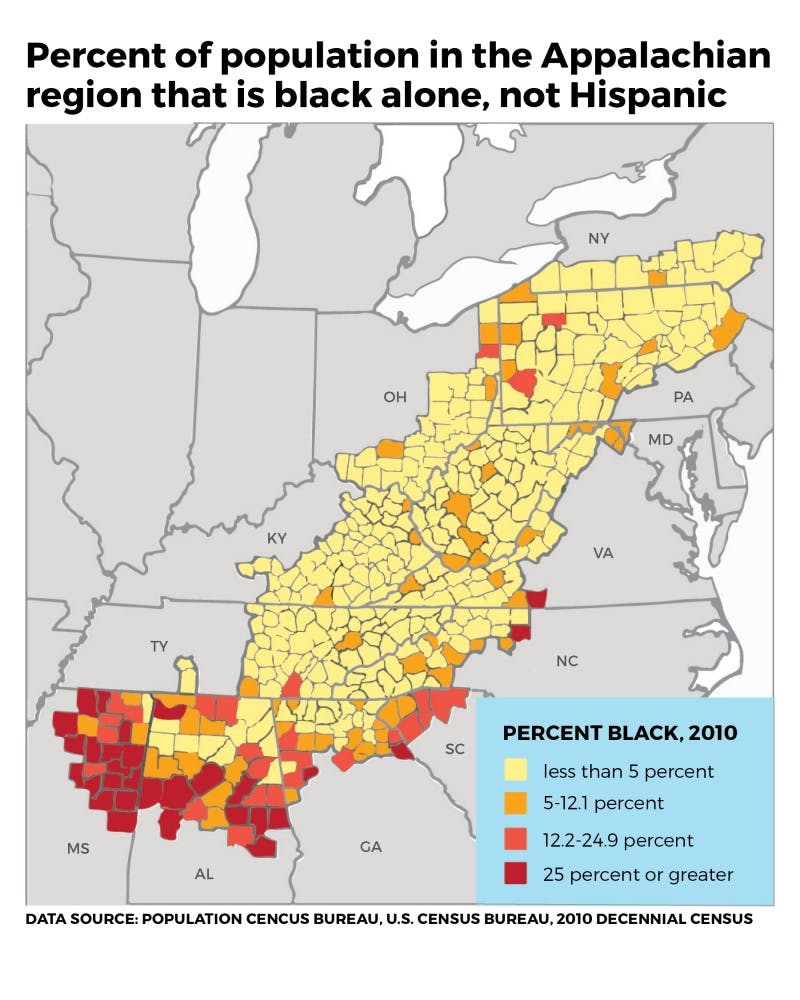

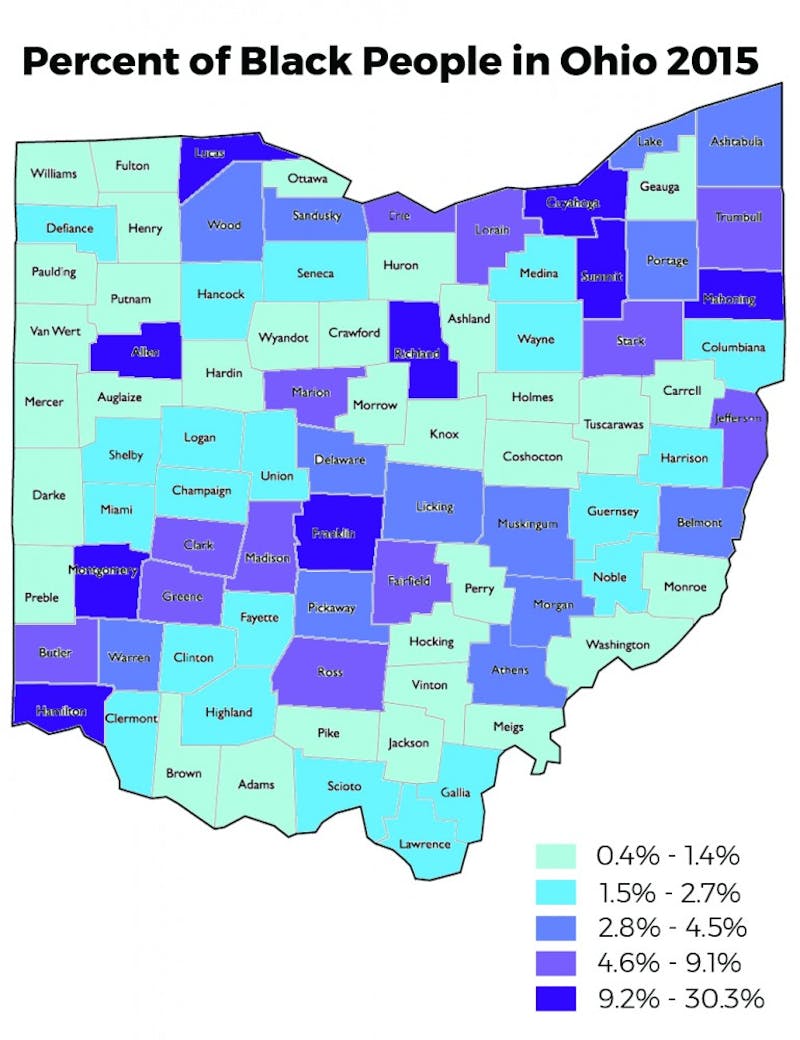

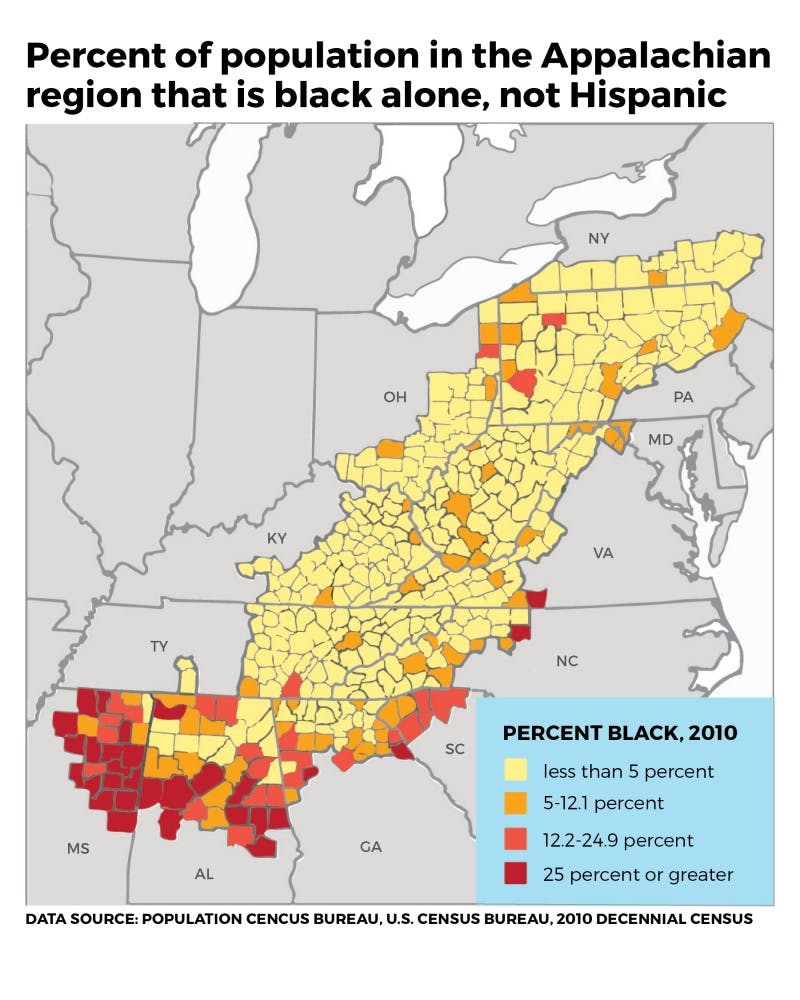

Black people, who make up fewer than 5 percent of Athens County’s population and 9.1 percent of the Appalachian population, have long been overlooked in an impoverished region that is overwhelmingly white.

“When people say we need to fix the white problem first, you can’t fix one without fixing both,” Ada Woodson Adams, a Nelsonville resident and 1961 Ohio University graduate, said. “When people say ‘Black Lives Matter,’ it’s a cry out that we have not been heard or seen, and we have been systematically institutionalized.”

Frank X Walker, a professor of English and African-American studies at the University of Kentucky, invented the word ‘Affrilachia’ in 1991 in response to the marginalization of black people in the region. He penned the word in a poem as a way to explain the “invisibleness” of Affrilachians.

“A lot of scholars quickly embraced the word because it allowed them to recognize that diversity had not been a large part of the conversation when we talked about the 13-state region that officially was Appalachia,” Walker said. “They embraced the word and began to recognize that they had missed something.”

White people make up 83.6 percent of the people in Appalachia in comparison to the national white population of 63.7 percent, according to 2010 U.S. Census data.

That lack of visibility creates a stigma against black people in Appalachia, Otis Trotter, the author of Keeping Heart: A Memoir of Family Struggle, Race, and Medicine, said. He spent a majority of his childhood in West Virginia before moving to Newcomerstown, Ohio in the ’60s, where he was subject to criticism because of his Appalachian and black roots.

“We still were looked on as black hillbillies,” he said. “They anticipated that we could be these typical black hillbillies, that we were unsophisticated and dumb.”

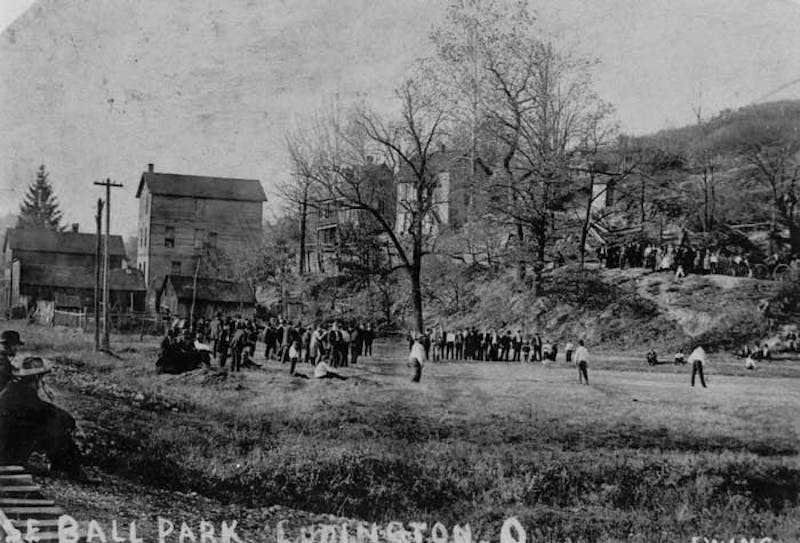

Provided via the Little Cities of Black Diamonds Council

Ohio’s de facto segregation was more subtle at that time than the blatant racism in the Deep South, Adams said.

“Going Uptown, we didn’t have the same places you could go and eat if you wanted to go to the restaurant with your friends, because they would turn you away,” she said. “There was no sign, but they would tell you you weren’t welcome there.”

A more glaring and obvious form of racial discrimination were so-called “Sundown Towns,” or communities that kept out black people by law. The term was coined because the towns would sometimes have signs by their city limits stating black people must be gone by sundown. Some of those areas remain very white to this day, according to James W. Loewen’s book Sundown Towns.

“Things like that affect the psyche of people black and white,” Adams said. “It diminishes the strength of a community when you have racism.”

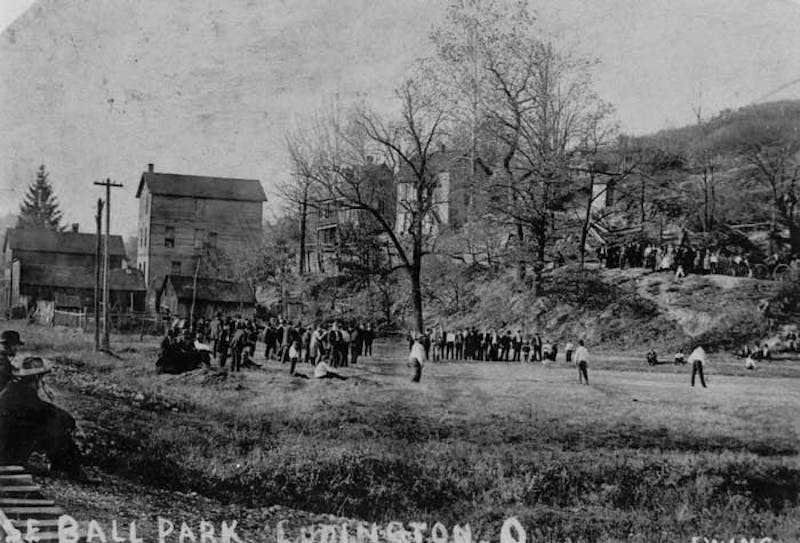

Provided via Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Penn State University Libraries

Major Fountain and children, Rendville, Ohio Perry County Ohio 1946.

Many black people migrated from the South to Appalachia to find work in the coal mining industry, as the Deep South lacked decent paying jobs for black workers. Trotter said his family moved from Alabama to West Virginia for that reason.

“My father was recruited by coal miners,” Trotter said. “He ventured out and tried to take jobs near where he lived, but he couldn’t find a paying job, so when the recruiters came, he took (them) up on (their) offer.”

A notorious integrated coal mining town was Rendville, located in Perry County. It was established by the Ohio Coal Mining Company in 1879, made up by primarily German immigrants and black families. Despite initial racial tensions, the town functioned much better than other integrated communities in Appalachia with a mixed race village council, Cheryl Blosser, office coordinator for The Little Cities of Black Diamonds, said.

The Little Cities of Black Diamonds is a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the history of coal mining regions.

“Rendville had a lot of opportunities and many other black miners moved there to work,” Blosser said in an email. “Because all of (the workers) were new and the miner owner paid the workers the same rate, some black families prospered better.”

Data used from U.S. Census Bureau

Though OU was relatively progressive during times of de facto segregation, problematic policies were still in place.

John Newton Templeton, a freed slave who earned his bachelor’s degree from OU in 1828, was the fourth black college graduate in the nation and first in the Midwest.

Templeton-Blackburn Alumni Memorial Auditorium on College Green is named for Templeton and Martha Blackburn, the first black woman to graduate from OU in 1916.

“It is nice that OU educated (Templeton). However, there are some stains on that,” Bailey Williams, a freshman in the Templeton Scholars Program, said.

Templeton could not live in university housing with other students, so he lived in the log cabin near the Hocking River that now houses the Office of Sustainability and the Visitor Parking Registration Center.

More than 100 years later, Adams faced similar discrimination. Adams, who began her freshman year in 1957, said she could not join social sororities or fraternities during her time on campus because of the color of her skin. She also could not complete her student teaching in Athens County because OU had an agreement with local schools that they would not send black teachers to instruct students.

Adams also noted subtly segregated areas on campus. For example, black students often gathered in a room in the student center called the “Bunch of Grapes Room,” which white students nicknamed the “Bunch of Apes Room.”

“We have to take the good with the bad,” Williams said. “I feel like a lot of our history gets washed down looking at the good. We have to take it for what it is and look at the good and the bad.”

Though incidents like the painting of a hanged figure on the graffiti wall in September have left a sour taste in Williams’ mouth, he said overall, he has not experienced discrimination because of the color of his skin.

“There is a good diversity blend here (at OU),” Williams said. “It’s not much, but what we do have, it’s diverse.”

Appalachians have made significant strides, Trotter said, but negative stereotypes surrounding those who identify as both black and Appalachian still exist.

“There is still a negative stigma,” Trotter said. “A lot of people tend to think about Appalachia as monolithic: They’re all white, they’re all poor. Many people still have that perception.”

The key to true integration of the region is to understand the differences among the population, Trotter said.

“We need to highlight a variety of people (from Appalachia) that are doing well, that are educated,” he said. “You can’t overlook that there are poor people ... but you also have to try to do something to make people realize that yes, you can be poor but also intelligent and diverse.”

Provided via the Little Cities of Black Diamonds Council

Provided via Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Penn State University Libraries

Major Fountain and children, Rendville, Ohio Perry County Ohio 1946.

Data used from U.S. Census Bureau

Landing Page

This story is part of a series of specially designed stories that represents some of the best journalism The Post has to offer. Check out the rest of the special projects here.